This year’s FA Cup should have been a classic, one that should have helped to relaunch the oldest cup competition in the world.

The Cup Final could not offer a more tantalising prospect. One of the finalists, Chelsea, could do the double, once such an elusive and an unfulfilled dream of many a great team. Its opponents, Portsmouth, could also do a double of a very different kind: the first team to be relegated and win the Cup.

Nor has there been a lack of giant killing in this year’s competition. It is hard to think of better examples of David slaying Goliath than Leeds going to Old Trafford and beating Manchester United or penniless Portsmouth coming to Wembley the day after relegation and beating Tottenham Hotspur.

Yet, far from adding lustre, the FA’s problem is that it just does not know what to do to stop its crown jewel from turning into paste. As Gordon Taylor, chief executive of the Professional Footballers’ Association, put it to me recently, “The FA is well aware that the FA Cup is the only jewel in their crown and is in danger of disintegrating.”

Taylor acknowledges, “This would be a sad thing because I think it’s a fantastic cup competition and we should do all we can to preserve it.”

To do that the FA will have to fight very hard but it knows that some of the problems which have done so much to devalue the competition are beyond its control. The whole shape of game has changed so dramatically in the last 20 years that the Cup no longer holds the position it once did.

Until the last decade of the previous century, the Cup had an unrivalled niche in the English football calendar. For a start there was its marvellously egalitarian base: all clubs from the amateur ones in Hackney Marshes to the mightiest in the land competing on absolutely equal terms. Then, with the clubs from the top divisions coming in for the Third Round on the first weekend of January, the competition was designed to give the game a much needed mid season boost.

By then, with nearly four months gone, the likely winners in the leagues could seek fresh glory while the likely losers could target the Cup as a consolation.

And there was always the possibility of great upsets. Those of us of a certain generation will never forget Arsenal fearing their visits to Yeovil Town or Don Revie’s Leeds getting a bloody nose in Colchester.

The Cup Final rounded it all off neatly. It was very often the final match of the season. It was the only domestic game played at Wembley, the only domestic game televised live and shown simultaneously both on BBC and ITV. Before the game everyone sang “Abide with Me” and after it everyone looked forward to the cricket season.

You only have to look back to the time when Taylor was a boy to realise what the Cup meant. Taylor can recall the 1953 Stanley Matthews’ final, “It was one of the first games I remember seeing on television. We walked a long way because my dad had a friend who had a television set.”

Being a Bolton man, he did not share in the nation’s desire for Matthews to win his first medal but he can still recall how that day’s events at Wembley brought the nation together.

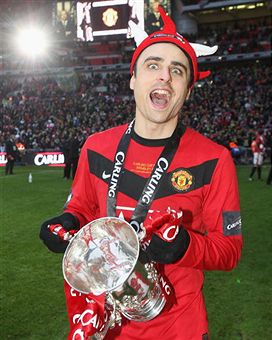

I cannot imagine that, even if Portsmouth under manager Avram Grant (pictured celebrating the semi-final victory over Tottenham) should somehow beat Chelsea this year, we shall have a similar sense of communal harmony.

I cannot imagine that, even if Portsmouth under manager Avram Grant (pictured celebrating the semi-final victory over Tottenham) should somehow beat Chelsea this year, we shall have a similar sense of communal harmony.

The fact is that the FA Cup Final is now just another date in a very changed football calendar. And with so much live football on television, it is no longer a special television event. Nor does the competition define the season any longer. The rise of the Premier League and the Champions League, whose final match now marks the end of the season, has played a big part in this.

It has also not been helped by the abolition of the Cup Winners Cup. This European competition was often dominated by English Cup winners, Tottenham starting the run of success in Europe for English clubs back in 1963. There was certain symmetry to it all.

To add to the FA’s misery, the League Cup, derided for years as Alan Hardaker’s unwanted baby, has revived itself. The crusty, insular League secretary’s desire to use the competition to divert English eyes from Europe may have failed. However, in the last decade as the FA Cup has grown old and sad, the League Cup has refused to die. If anything it has made its place secure and created a very interesting niche.

Resuscitation was helped by making sure winners qualified for Europe. But the League also alleviated the crowded fixture list by streamlining the competition. This has included seeding clubs in European competition to Round Three, removal of replays from all rounds and ending of two-legged ties in Rounds One and Two.

Not many in the game had a good word to say when Alex Ferguson and Arsene Wenger used the competition to blood youngsters. But it has meant that a new generation of young fans see a new generation of young players, all the more attractive given that young players in a big team do not get many chances.

And, while the big clubs may not always field their first teams, the competition is dominated by the big names. The last six finals have featured Chelsea and Manchester United on three occasions, Spurs twice, and Liverpool and Arsenal once each. And, with the final in February, the competition has created a niche in the calendar at the same time as the FA Cup has lost its niche. If crowd figures are any guide it has worked. Ten years ago average crowds were 9,700. This season crowds averaged 14,900, the highest levels for more than 30 years.

And, while the big clubs may not always field their first teams, the competition is dominated by the big names. The last six finals have featured Chelsea and Manchester United on three occasions, Spurs twice, and Liverpool and Arsenal once each. And, with the final in February, the competition has created a niche in the calendar at the same time as the FA Cup has lost its niche. If crowd figures are any guide it has worked. Ten years ago average crowds were 9,700. This season crowds averaged 14,900, the highest levels for more than 30 years.

The League can also claim that the Carling Cup does its bit to narrow the huge financial gap with the Premier League: around £35 million ($54 million) of the £50 million ($77 million) generated annually is distributed to Football League clubs, with the bulk of the money going to Championship clubs.

True the FA has tried various innovations to revive the Cup, such as introducing prize money.

But unlike the League, the FA’s constantly shifting management board has taken decisions which have turned out to be quite disastrous.

Allowing Manchester United, the holders, to drop out of the competition to help a doomed England attempt to stage the 2006 World Cup was not very clever. Building a costly Wembley then using it not just for the finals but also the semi-finals has done much to remove the unique mystique of the final. And Setanta’s collapse meant the decision to shift television coverage from BBC/Sky to ITV/Setanta is proving financially very costly indeed.

To add to its problems the FA, in this tough economic climate, is looking for a new sponsor for next season. In contrast the League can claim with some pride that its current sponsorship partner Molson Coors has been with it for 14 seasons (five years of Worthingtons and nine years of Carling).

The real strategic issue the FA faces is realise that the Cup can no longer hope to share centre stage of the English football world as it did for more than a century. It still has a place in the football calendar but it is a much reduced one. The FA now needs to define very carefully what that place is. Then it may have realistic hopes of securing it. If it continues to behave as if it can lord over the castle, more grief lies in store.

Mihir Bose is one of the world’s most astute observers on politics in sport and, particularly, football. He formerly wrote for The Sunday Times and The Daily Telegraph and until recently was the BBC’s head sports editor.

.jpg)