The Carlos Tévez and John Terry affairs could not be more different. One is a case of an employee allegedly not wanting to do his job; the other is about an employee allegedly behaving badly while at work.

They both illustrate the behaviour problems of today’s footballers, more so during high profile matches which are subjected to unprecedented public scrutiny through the internet and social media.

They also illustrate that those involved in running football including the players union, the Professional Footballers Association (PFA), have not moved with the times.

Many of these football organisations are still caught up in a 60s time warp. Then YouTube, if the word meant anything, would have been thought to be a dental floss and twittering something that kids were admonished for doing in front of grownups. To be fair, the public reactions to both events suggest we may all be obsessed with the past, judging these modern events through the prism of a discarded periscope.

Take the Tévez affair. This is building into a classic “he said, she said” story. Tévez says he did not refuse to come on as a substitute but merely refused to warm up. Manchester City insists he did. There are all sorts of issues involved here, not least language, and it may well require a court case to decide what actually happened. But, the fact that Tévez can contemplate court action with all the money this needs, shows that many of the modern high profile players are more like rock stars than employees. The average football fan may still see a footballer as an employee of a club but, for players like Tévez, their relationships with their managers have little in common with most employment situations.

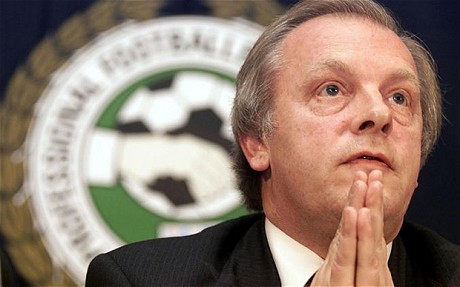

And this is where the role of the PFA gets so curious. Its chief executive Gordon Taylor (pictured below) represented Tévez in the hearings but when City wanted to impose more than the statutory two-week fine, which requires PFA approval, the union refused to give it.

The PFA has always been the most remarkable union, with members like Tévez earning in a week much more than most other PFA members earn in a year. More than that, unlike any other union, the PFA has a role in the management of the game. Indeed, it can even decide which players a club can employ. So, before the Home Office allows a footballer from outside the EU to play here, it has to consult the PFA’s guidelines, which specify how often a player must have played for his country and the ranking of the country. It is only after these criteria are met that the player can be given a work permit. Imagine the plumbers’ union being asked if we could import plumbers from non-EU countries. The idea would be laughed out of court.

The English game may never have accepted the sporting socialism that Americans embrace but, before the emergence of the Premier League, there was an equality of sorts in English football. The PFA’s rise and its powers reflect such a time. Indeed, it was the injustice felt by the big clubs, like Manchester United, at earning the same as Rochdale for being on television that spurred the creation of the Premier League.

The PFA’s historic role in looking after footballers when players were essentially wage slaves cannot be denied. However, as the Tévez affair shows, it continues to react as if we have not moved on from the days of the maximum wage. Tévez may be a union member but to consider that he is on a par with say a Rochdale player is manifestly absurd. Yet the PFA persists in that belief.

Now Taylor, who remembers with great clarity how football was when he was growing up and how wretchedly players were treated by clubs, will argue that there is no other way. Yet it is interesting to compare the PFA with the civil service. All civil servants, including the Cabinet Secretary, belong to a union. But, and this is crucial, they do not belong to the same union. While the number of unions in the civil service has slimmed down, there is still a union for the big shots, including the Cabinet Secretary, called the First Division Association, the name clearly reflecting football as it used to be before the Premier League came about. The others are in the Civil and Public Services Association (CPSA). There was a time when there was even a civil service clerical union but this has since been consumed into the CPSA.

For the PFA to voluntarily accept that it cannot be an umbrella union for all footballers may be like asking turkeys to vote for Christmas. There was a time, a decade ago, when foreign players did not belong to the PFA and required no little persuasion to join. The fact that Tévez belongs to the union shows the PFA’s recruitment drive has worked. Yet the union needs to recognise that football has changed. Its claim to represent everyone is a bit like having one union in the civil service. It is just not on.

A union more attuned to the very different needs of a high profile player would, I believe, have ensured that the Tévez affair did not descend into the farce it is threatening to do.

To call another player racist is no joke but the reaction to what Terry may or may not have called Anton Ferdinand also shows how much the past is affecting us. And, in this case, the dark shadow of racism from the 80s seems still to loom over the game. Observe how quickly everyone has talked about what it was like in English football back in that awful decade. I remember it all too painfully. As a reporter for the Sunday Times, I was often the only non-white face among the spectators and to go into a football stadium was like going into a battlefield. One had to prepare carefully to ensure one merged intact.

It was made worse by the fact that the football authorities and much of the media turned blind eye to it. Then entire football stadiums seemed to be filled with racists and, in Brian Glanville’s memorable, if chilling phrase, evening matches at Stamford Bridge were like Nuremberg under the Nazis. I remember arriving at Ipswich to report a match and being accosted by National Front Supporters shouting, “Get your colour supplement here.”

We have thankfully moved a long way from that. There are supporters who are racist but they are not tolerated inside grounds, let alone allowed to dominate them. If Terry is indeed guilty of racist behaviour, then what it might suggest is that racism may have moved from supporters to certain players.

If that is the case, then it raises some very serious questions. Players like Terry would have grown up in a multi-racial football world. For them to believe a player is defined by the colour of his skin would lead to the dismal conclusion that, in this case, familiarity does breed contempt not togetherness. Given how multicultural we are, that would be profoundly worrying.

I hope that is not the case and that whatever was said was an isolated incident.

But what is crucial in both affairs is that we recognise how the game has changed. Unlike generals who always fight a war with weapons from previous wars, we must not fall back on the past to remedy the problems of the present.

Mihir Bose is one of the world’s most astute observers on politics in sport and, particularly, football. He formerly wrote for The Sunday Times and The Daily Telegraph, and was the BBC’s head sports editor. Follow Mihir on twitter.