Here we go again.

England needs a new football manager, setting off a new cycle of speculation, unrealistically burgeoning expectations and disillusionment, as surely as, well 55,000 Twitter-users follow the Anfield cat.

Actually, the speculation bit looks like being much diminished this time, since everyone thinks they know the new man’s identity: step forward Harry Redknapp, cheekie-chappie manager of Tottenham Hotspur, surprise package of the 2011-12 English Premier League season.

But I see ominous signs of the rose-tinted spectacles that one might have thought consigned to the outer darkness for good after the South African debacle being rummaged around for and even dusted off in readiness for Euro 2012.

The rest is only a matter of time.

We, by which I mean we English folk, need to get one thing into our sweet little heads: if the national football team manages every four years to reach the quarterfinals of the World Cup and the semi-finals of the European Championship, that is punching our weight, arguably rather more.

If more of us understood that – and I mean really understood in our entrails and our bones – an awful lot of national angst could be avoided.

Of course, this should not entail expunging our right to hope for more.

But that, broadly, should be the benchmark; anything better, though I use the word cautiously in the present climate, should be interpreted – and appreciated – as a bonus.

That said, you have to concede that other countries with similar populations and levels of economic development – I’m thinking France, Italy, Spain – have enjoyed their moments in the sun far more recently than England’s solitary efflorescence, on home soil on a Wembley afternoon now so long ago that even I can only just remember it.

So it can be done, but how?

Having thought about this, I reckon there are three routes to punching above your weight in international football.

1. You can be lucky enough to have the world’s best player on your team. I’m thinking Brazil 1958 and Argentina 1986, although the present Argentina’s failure to capitalise on Lionel Messi suggests this may no longer be enough.

2. You can develop a system that is more efficient than anyone else’s and school your players religiously in its implementation. I’m thinking the present Spain and their elevation of ball retention to a sacred tenet. The trouble here is that systems giving you that much of an edge are creatures of extreme rarity. Their value, moreover, starts to be eroded the moment your rivals start copying you.

3. You can study your opponents in great detail and craft a plan to neutralise them. The best example of this I have witnessed in recent times was the victory of Ottmar Hitzfeld’s Switzerland over Spain in Durban in the 2010 World Cup, but I wonder if something like this doesn’t also explain the success of Bert van Marwijk’s Holland, who seem in many ways very ordinary.

Route three is both the most controllable and the most accessible, and is of course practiced by every international team worth its salt, at least on a match by match basis.

But what happens to all that priceless intellectual property at moments like the present in England when the old manager and his entourage depart?

My hunch is that a big part of it goes walking out the door and, in doing so, helps to perpetuate English football’s eternal cycle of drab mediocrity.

I usually hesitate before resorting to World War II imagery to reinforce my points, but in this case, I hope that to do so is neither overly nationalistic nor offensive.

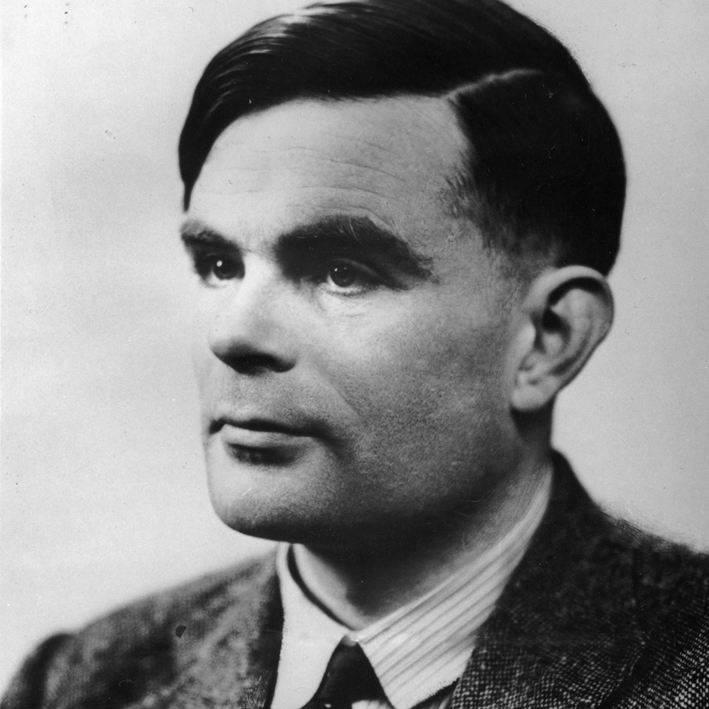

I will posit the analogy in the form of a question: if Redknapp is to be English football’s new Montgomery, who is its Alan Turing?

Turing, many will recall, was the man at the heart of the celebrated Bletchley Park code breaking operation that put information on the enemy’s plans and resources at the fingertips of allied generals and played a key part in determining the war’s outcome.

Perhaps the Football Association already has a football Turing, squirreling away secretly in a draughty Nissen hut in the Wembley car-park, continuously analysing every nuance of the on-field tactics of the world’s top 30 international football teams and rooting out intelligence on significant off-field innovations.

If it does, this piece will have done no harm; if not, then it needs one – and the belated completion of St George’s Park affords a good opportunity to make the appointment, surround him – or her – with a top-notch secretariat and keep them all in a style befitting their importance.

Just one thing – though their work would of course be made available to the England manager du jour and, I think, be of great assistance, their function and appointment should be kept entirely separate.

That way, when the manager walks, the accumulated data-bank stays.

If you are sceptical about the wisdom of this, or the difference it might make, try thinking about it this way.

Since that increasingly forlorn footballing triumph of 1966, British sport has delivered two further peaks of achievement which, while they cannot quite match that Everest, are like K2 and Annapurna 1.

The England rugby World Cup win of 2003 was masterminded by a figure, Sir Clive Woodward, who had something of both the Montgomery and the Turing about him.

The astonishing Team GB medals haul at the Beijing Olympics in 2008 definitely did feature its Turing – Peter Keen of UK Sport.

If Britain again exceeds expectations this Summer in London – though to do so to the same extent would be, quite frankly, impossible – I shall rest my case.

David Owen worked for 20 years for the Financial Times in the United States, Canada, France and the UK. He ended his FT career as sports editor after the 2006 World Cup and is now freelancing, including covering the 2008 Beijing Olympics and 2010 World Cup. Owen’s Twitter feed can be accessed here.