By Paul Nicholson

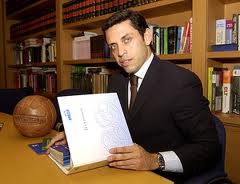

June 14 – Neymar’s lawyer Marcos Motta says that if the European push for the banning of third party ownership of players is successful, and applied globally, then it could lead to a collapse of football on the South American continent. When Motta, founding partner, Bichara e Motta Advogados and one of the leading football lawyers in South America, takes his seat on the panel at the FT/IFA one-day conference at the Copacabana Palace Hotel, Rio de Janeiro, June 17, you can expect there to be fireworks. And any Europeans in the room could feel a little uncomfortable.

Motta does not mince his words. “UEFA are going beyond their jurisdiction and competence,” he says. “They are taking no account of local specificity and how football is financed in each market. Third party ownership is the hot international topic right now and it needs to be addressed properly with a full understanding of what it actually means.”

Motta has recently returned to Brazil following a trip to Europe that saw him attend the Champions League final in London, speak to leading sports lawyers in Paris, and complete the move of Neymar from Santos to Barcelona. He is no stranger to dealing with Europeans, having negotiated deals for Carlos Tevez, Lucas to Paris St Germain, Fernandinho to Manchester City, Thiago Silva to PSG and Robinho to Real Madrid and many more besides.

“What you must understand is that in Brazil and South America we do not have the revenues and assets of the European clubs,” says Motta. “We don’t get €40-50 million from sponsorships or such high gate receipts or television deals. Our clubs must be helped by the assets they do have which are their players…People talk about slave trading. They don’t know what they are talking about. Nobody can oblige a player if he doesn’t want to move.

“Let me tell you something. Of the 11 players that started for Corinthians in FIFA’s World Club Championship final against Chelsea, at least 10 of them were co-owned or co-shared amongst investors. Without the investors there would have been no Corinthians in Japan.”

In South America top players will generally sign their first contract with a club at 16. It is at this stage that investors will acquire shares in the player’s economic rights, with the club benefiting from the arrangement financially. The clubs generally participate in the future earnings of the player as well. For investors it can be a risky business, not all players go on to become world beaters. “There can be fantastic returns,” says Motta. “But there can sometimes be fantastic losses as well.”

But there are problems with third party ownership and Motta recognises and encourages more transparency in these deals. The first step, he says, is to “study the market and make a global approach. I think FIFA have the right approach at this time in this regard. Of course it is important to keep the influence of third party ownership under control. We have to preserve the competition. No-one is arguing against that.”

The issue of who actually controls the players and owns their image rights does differ between markets and throws some interesting questions of definition. For example, Major League Soccer in the US hires all its players centrally and then distributes them to the clubs. But the MLS is not a club. Is this third party ownership by another name?

“In South America we want stronger leagues,” says Motta. “We need investment and revenues. Our assets are our players rights and we are exporters of players. We are not selling people. I am talking about their economic rights…Maybe managers who complain do so because our players are not so cheap as they used to be.

“Things are not the same as before. Football has changed. There are investors and there are new sources of revenues, better deals and better proposals. When we are selling we are selling for the investors, but this includes the club and the player. The market is safe and it encourages new investment and keeps money within the game. Perhaps it can be a little better regulated. But understand this. We are talking about a financial tool used by South American clubs to build their clubs.”

Following the Neymar sale there has been a dispute over the money and its distribution. “This is a dispute between investors. It has zero influence on the player. It is clearly a commercial discussion and is nothing related to the playing of the sport,” says Motta.

But what about the sale of Tevez to West Ham. There were a lot of disappointed people then. “Tevez moved to West Ham, there was nothing illegal in that. There were sanctions not because the deal was done but because it wasn’t disclosed.”

Motta will be taking on all-comers at the FT/IFA conference on a panel focused on the future of Brazilian football, June 17 at the Copacabana Palace, Rio de Janeiro.

Contact the writer of this story moc.l1745633773labto1745633773ofdlr1745633773owedi1745633773sni@n1745633773osloh1745633773cin.l1745633773uap1745633773