“I am the lord of the philosopher’s stone,” Mammon, The Alchemist, Ben Johnson

Four hundred years after those fictitious words were first uttered on a London stage, alchemy, the fabled process of turning base metals into gold, is of course just as much hocus-pocus as it was then. Even so, it does not seem to have stopped football clubs trying to turn leaden-footed footballers into the latest golden generation. Their alchemic additive is of cash, since the relative amount of wages paid to first-team players closely correlates with League finishing positions.

But the fact is there are very few gold-plated investments in football. Owners of less-glittering clubs who try to keep up with the best too often reverse the alchemic process by pouring riches into ultimately worthless investments. As the January transfer window opens for trading across Europe, those seeking to preserve their top-division status, push for promotion or Champions League qualification or perhaps clinch a title will be hard at work in their data laboratories considering what elements would bring success as an admixture to their squads.

Yet football, like most things, is governed by different forces: economics and the financial gravity it exerts. One apple that has fallen from the tree with a thump is Bolton Wanderers. The Greater Manchester club’s relegation from the Premier League in 2012 came after years of vain effort to inflate its prospects with shareholder sustenance.

Now, with the filing of the Trotters’ 2012-3 season accounts, we can see what damage falling out of the top flight has wrought. In simple terms it slashed £30 million from the club’s income at a stroke. Despite their receipt of £15.575 million of ‘parachute’ payments from the Premier League, broadcast revenues were cut in half from £42.562 million to £19.1 million.

Gate receipts fell by £2 million or more than a third, corporate-hospitality revenues were down £727,000, being more than 40%, while merchandising income fell by a similar quantum and proportion. As for sponsorship revenues, they attained less than a third of their Premier League levels, down from £4.255 million to £1.379 million. There were some bright spots. Somehow, despite the near-25% drop in average attendance – from 23,670 in the Premier League to 18,093 in the Championship – revenues Bolton earned from their on-site hotel remained unchanged at almost £6.5 million, which must have come as a surprising good fortune.

Otherwise, the club’s straitened circumstances were so sudden and so severe that the ensuing austerity measures could not prevent them haemorrhaging cash like blood from an arterial wound. Wages fell, with the chairman, Phil Gartside, suffering a £450,000 drop in his own salary and benefits as that came down almost 50%. But the cuts in the overall wage bill saved only £17.926 million, substantially less than the £23.5 million drop in broadcast revenues.

Work was clearly done to reduce running costs, with operating cash expenditure falling more than £22 million. Yet the £55.8 million in operating-cash spending can still be regarded as a staggeringly high sum: in 2012, the year before they won the FA Cup, Wigan Athletic’s entire turnover had been less than £52.6 million, and even after player trading their total cash spend was less than £53.4 million.

Indeed, in an apparent effort to recover the riches of the Premier League, there was £6 million of gross investment in the transfer market, with less than £1.3 million recovered from the departures of Martin Petrov and others. Yet the spending on transfers went almost exclusively on players who had failed to win promotion from other Championship clubs and it was perhaps small wonder that Bolton failed to make the play-offs in 2013, deprived as they were by Leicester City when they managed only a 2-2 draw at home to Blackpool on the season’s final day. (Coincidentally, a similar scoreline had sent them down the previous season.)

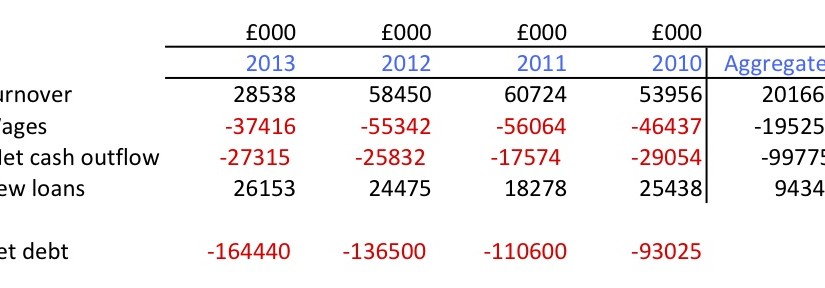

It all added up to cash overspending of £27.315 million over the 2012-13 campaign. This came on top of £25.832 million the previous year, £17.574 million the year before and £29.054 million the year before that: a mere £225,000 short of £100 million in cash disappearing down the drain in the name of Bolton Wanderers: at time of writing they are the 18th team in the Championship.

Bolton key financials 2009-2013

Source: Bolton Wanderers Football & Athletic Company Ltd/Burnden Leisure PLC

It is easy to write or read such numbers without considering the true impact of such extravagant expenditure. When people justify obscene overspending on clubs in glib terms about the vicarious pleasure owners gain from spending huge sums on football clubs, then it would be worth balancing that against the pleasure Bolton’s 116,400 households would have felt upon each receiving a gift of £850 through the door rather than for it to have been ploughed into the local club over the prior four years.

What do Bolton’s owners really get out of it? Certainly less now in the Championship than when it was a Premier League club. Prior years’ cash losses have at least been offset by millions of pounds in interest on shareholder loans (£5.517 million in 2012, £6.940 million in 2013) but the terms have now been changed such that no interest is chargeable on the debt.

The size of the debt is alarming, although whom it is owed to is not entirely clear. Eddie Davies, an industrialist, is frequently referred to as the owner of the club, but its ultimate parent company is Fildraw Private Trust, based in Bermuda, where it was incorporated in June 2006. Moonshift Investments Limited is Bolton’s immediate parent company and principal lender, with six outstanding loans in the club. Davies is declared as having “a beneficial interest” in this offshore entity, though where it is incorporated is unclear. The company by the name of Moonshift Limited registered on the Isle of Man (where Davies’s electricals company, Strix, is based) was dissolved in March 2011. There is a company in Bermuda by the name of Moonshift Properties though it is not immediately obvious this has any links to Bolton.

Still, Gartside has this week been at pains to reassure Bolton fans that all is in order in their preposterously indebted and (but for the support of their offshore lenders) cashflow-insolvent club. “Technically it is a debt but it’s not in the sense of a bank debt,” he told BBC Radio Manchester on Monday.

“It doesn’t cause me any sleepless nights. It is an amount of money that a benefactor has lent to us. It’s not a bank debt. If some other foreign owner does that sort of thing, it would never get a mention. Because it’s Eddie Davies and because it’s Bolton Wanderers, it gets called debt.”

For all Gartside’s insouciance, if it is Davies alone who holds the debt behind the offshore veils then it must be giving him sleepless nights. According to a report in the Financial Times in 2011, the target for Davies’s electrical-elements firm, Strix, was for annual sales of £100 million in 2013. If this was accurate it means that Strix’s hoped-for overall turnover for 2013 – forget profits or cashflow – pretty much equalled what now-relegated Bolton had consumed in cash from its shareholders in the four years between July 1, 2009 and June 30, 2013.

The best you can possibly say about all that money is that it has turned out to be fool’s gold.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745071329labto1745071329ofdlr1745071329owedi1745071329sni@t1745071329tocs.1745071329ttam1745071329.