“Hail, thou that art highly favoured… blessed art thou.” Archangel Gabriel to Mary; Luke 1:28

It has been a purgatorial 12 months or so for Manchester United. So if you are a supporter of theirs it must be tempting to look to a man named Angel Di María as some sort of celestial deliverer for your club. Sure, one Angel does not make a host but it should not be too hard for a £59.7 million player of his quality to make an impact.

The (albeit benched through injury) World Cup finalist joins a club that did not qualify for the Champions League and which has one point from two Premier League games. Now they are out of the Capital One Cup – humiliated 4-0, by a side 38 league places below them to boot. Surely in this context we should think not so much about what Di María can do for United but what can United do for him.

It seems from Di María’s open letter to Real Madrid fans this week that much of what he seeks from his employer is an emotional benefit. “I’ve always wanted to progress, as anyone else does in their job,” he said. But then even he admits some of it is down to cold, hard cash. “The only thing I asked for was a fair deal,” he added. “There are many things that I value and a lot of them have nothing to do with my salary.” Some, though, evidently do.

The answers as to how United accommodate a man used to the accoutrements of being a neo-Galáctico at the Bernabéu lie in a document sent out to investors relating to the sale of shares earlier this month. (United fans dislike the controller-shareholding Glazer family for their corporatisation of the club. But for the rest of us the enforced transparency of their repeated bond and share issues has provided fascinating insights into Old Trafford and the football business at large.)

In it, using the American English of the controlling dynasty and of the New York Stock Exchange where the club’s shares are listed, United make clear: “To maintain our high standard of performance we anticipate a higher level of net player capital expenditure and player wages to retain talent and enhance the caliber of our team in the near term.”

Hence the British-record outlay on Di María. But even before signing him, Luke Shaw, Ander Herrera and Marcos Rojo, United owed £72 million in cash to other clubs over the course of the next 12 months. Over the following year or so another £25.7 million is also owed. It means United are now committed to paying out more than £200 million in cash over the next year or two. There is also the compensation payment for the sacked former manager David Moyes, estimated by United at about £5 million, to consider. There are other cash-hungry investment activities: in infrastructure (about £5 million this year) and digital-media support (c£2-3 mllion a year). Running a football club of Manchester United’s stature does not come cheap.

Still, much has been spoken and written about United’s commercial incomes and with headline sponsors such as Chevrolet and adidas committing tens of millions of pounds each every year, that is quite right. But as Moyes’s successor, Louis van Gaal, seeks to “build a new team”, how much investible cash will he have at his disposal?

Let’s go through those commercial incomes first. The new adidas deal is worth about £75 million a year. United say this is the minimum guaranteed payment but the sales achieved last season by Nike, a bigger company than adidas, did not trigger payments above those minimum guarantees. It is fair for now to assume adidas will not either. The effect of the new deal will not in any case be felt until next season and, deferred payment schedules notwithstanding, this season’s revenues are what the bulk of the current spending will be covered by.

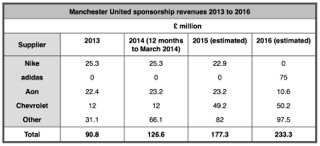

Here are the figures according to reported numbers from the 2012-13 season and reasonably projected for deals already announced:

These are very substantial sums and once other commercial, match-day and broadcast revenues are thrown in, United’s overall 2013-14 revenues exceeded £420 million. So what about this season?

Although the Chevrolet title sponsorship and additional lower-tier partnerships have significantly raised income from those streams, with no European nights to count on in the absence of Champions League or Europa League football, Nike’s kit-supplier payment to United falls by almost 10%. Indeed as it stands Old Trafford will lie fallow on weeknights all season following the Capital One Cup exit. This takes away up to £25 million of potential additional match-day income (although realising that figure from European and midweek cup games would probably have required runs to the semi-final of both competitions).

Last season’s Champions League quarter-final appearance earned more than £35.5 million in UEFA broadcast payments alone and they will see none of that this year. They must also improve on last season’s seventh-place finish to reduce the £7.5 million-plus gap with what the first- and second-place clubs derived from the Premier League in broadcast payments.

Suddenly, the increase in turnover from sponsorships does not look so substantial. It could even be wiped out altogether by these missed incomes. And yet the costs keep rising.

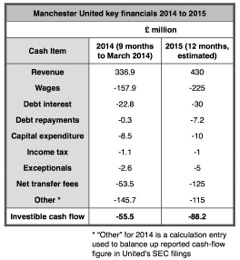

Wages and salaries rose 11.6% year over year from 2012 to 2013 and, despite the departures of high earners like Rio Ferdinand, Nemanja Vidic and Patrice Evra, these are unlikely to have fallen. Especially if Jose Mourinho is right in hinting that the 19-year-old Luke Shaw is earning £6 million a year. At the end of 2013 the salary bill stood at £180.5 million but with new deals in place for Wayne Rooney, Michael Carrick, Phil Jones, Antonio Valencia, Adnan Januzaj and others including the new signings, it has since risen dramatically. In the 12 months to March 2014, the wage bill hit £209.1 million. This season (2014-15) it is likely to be similarly ranged between £200 million and £225 million.

This offsets the advantages United’s board worked for itself in a painful restructuring of the club’s debts in 2013, which led to £26.5 million in one-off costs to lenders. Although it reduced the overall interest bill from about £47 million a year to about £30 million (provided bank rates do not rise sharply in future) the saving is swallowed up by the rising staff expense.

It all adds up to a club that has been seeping cash due to unforeseen difficulties on the pitch and a scrambling effort to restore themselves to their lofty former status.

The substantial cash outflow in the 2014 column in the table above might alarm United sympathisers and investors but there is considerable relief here. Between April and June, unaccounted for in the 2014 numbers above, the club receive “significant payments from major commercial agreements.” These are high-margin revenues and in 2013 £85.1 million was generated in the quarter, creating £73 million of cash. It is fair to extrapolate that in the equivalent period for 2014 United will have generated about £100 million in cash, producing a likely full-year cash inflow of probably £45 million and taking their overall cash balance to £140 million.

It must also be stressed that although for the 2014 column the entries in the table above are drawn or calculated from United’s reported figures it makes a number of assumptions that mean the accuracy of the 2015 figures cannot be guaranteed. These are that revenues (perhaps generously) assume a return to fourth place in the Premier League and there is an inference of a strong degree of wage inflation which might not arise. Most of the other items are as reported; however, debt repayments are discretionary and the £7.2 million is the base case – the club may repay up to £4.7 million a year on top of that sum depending on the amount of free cash it has available. But, as we can see from the table above, there is a diminishing amount of that.

If the sums above are correct then in 2015-16 there will still be about £75 million on existing transfer commitments, even before Van Gaal invests in the defensive midfielder he craves. As things stand the 2015 cash balance could already be set to drop to about £50 million on existing commitments alone, suggesting there is not much spare room for United to manoeuvre. It also reduces their transfer-market flexibility in future windows.

What should occupy the thoughts of the board even more, given these straitened times on the pitch, is the lumpy payment due on their secured loan in 2018. Between now and then United may only have repaid £18.8 million of the £186.8 million currently outstanding. Repayment of the £168 million balance will be due in full on 21 June 2018 and shareholders are unlikely to appreciate dilution of their equity with a stock-market fund raise.

So United have three options ahead of them. One is to sell unwanted players like Shinji Kagawa, Javier Hernández and Wilfried Zaha, which might raise a few tens of millions. Another is recourse to “our revolving credit facility agreement” which permits borrowing “up to £75 million from a syndicate of lenders and J.P. Morgan Europe Limited as agent and security trustee”, although that only lasts until 2016. The third would be to send the club on a money-spinning globe-trotting tour. Despite Van Gaal’s public objections to this strategy, it looks the likeliest outcome.

“We undertake exhibition games and promotional tours on a global basis, enabling our worldwide followers to see our team play,” the club said in its statement to investors. “These games are in addition to our competitive matches and take place during the summer months or during gaps in the football season. Over the last 4 years, we have played 21 exhibition games in Australia, China, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Japan, Norway, South Africa, Sweden, Thailand and the United States.”

United do not even privately deny that it is under consideration this season, given the number of “gaps” that have now opened up. This could raise huge money from foreign facility fees, merchandising and gate receipts and could lift proprietary media revenues (currently £17.6 million, or 9.6% of commercial income) very substantially. But costs will also rise as the first team travel first class and en masse to delight their worldwide followers in the flesh.

So these are the problems Manchester United face. But it has to be noted that few are so fortunate as they are as to have the opportunity to turn the otherwise-disastrous absence of Champions League football into a lucrative opportunity. To be so highly favoured, this club truly are blessed.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745599010labto1745599010ofdlr1745599010owedi1745599010sni@t1745599010tocs.1745599010ttam1745599010.