“There can be only one,” Connor MacLeod, Highlander

Arsène Wenger might have you believe that competing in the Champions League matters; that an attractive style of play is important. But he is wrong. Football today is all about winning, and as a graduate in economics he should know that.

This is the message that shines through from the most recent financial results announced by three of Europe’s top clubs. Let’s start with Bayern Munich, whose financial highlights for the year ending 30 June 2014 were announced last week.

It was a record year for the German champions who won their 24th domestic league, doubling it with a 17th German cup triumph. They also reached the last four of the Champions League. The combined football success generated €528.7 million (£418.5 millon, $657.6 million) of turnover for Bayern.

Regrettably there is no detail in Bayern’s release to break down how the money was earned, but there are clues elsewhere as to the provenance of the club’s money. In 2012-13, a treble-winning season that included Champions League success, Bayern generated 55% of their €431 million (£341.8 million, $536.4 million) income from commercial contracts. Although this may have fallen as a proportion of their total revenues following the 22.7% growth in turnover, it is still the most significant contributor to what the club earns.

“There’s no question that our FC Bayern is based on unprecedented sporting and commercial foundations,” Bayern finance chief and deputy chairman Jan-Christian Dreesen said. So assuming there is still close to half of the club’s overall income drawn from commercial contracts, Bayern’s 2013-14 sponsorships would be worth about €240 million (£190 million, $300 million).

Bayern are providentially assisted in having key commercial partners who also have substantial shareholdings in the club. Adidas (kit supplier), Allianz (stadium naming-rights sponsor) and Audi (tier-one sponsor) each own 8.33% of the issued share capital in the club, permitting a form of equity financing on commercial terms. But their association has not led to venal extravagance from sponsor-shareholders – the material value of Bayern’s football success is reflected at the other dominant clubs in the European market.

Real Madrid are the current European champions having won their elusive “Décima”, the club’s 10th European Cup or Champions League trophy, last season. Their financial report is a similar triumph. Turnover rose 5.6% year-over-year to €550 million (£436.6 million, $684.2 million), which represents a remarkable compound annual growth rate of 12% since the 1999-2000 season. (Over the same period the S&P 500 market index of US stocks rose 3.55%.) And as is the case for Bayern, the largest revenue-generating segment of Real’s operations is the commercial area, worth €174.6 million (£138.6 million, $217.1 million) in 2013-14.

The tale is similar at Manchester United, the pre-eminent club in the world’s richest league. Turnover was £433.2 million (€545.8 million, $678.4 million), with 43.7% of it (£189.3 million, €238.5 million, $296.5 million) coming from the commercial segment. It is clear the value of their commercial sponsorships is a consistent trend between all three of these European behemoths.

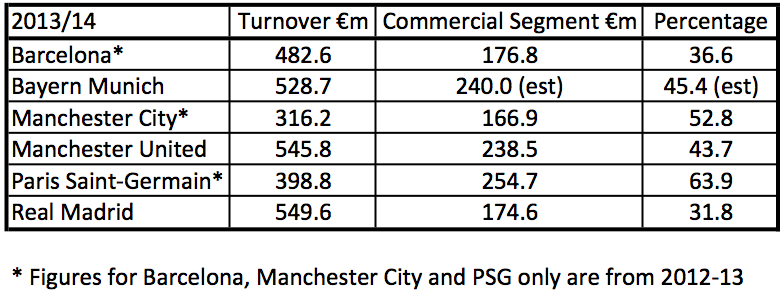

European football’s highest commercial incomes

The table above shows the six highest-earning clubs in Europe by commercial income. First it is worth noting that although Real are the men of the moment in Spain, their shadow is not cast over Catalonia, where Barcelona can also be considered one of the four undisputed champions of the European commercial scene. Atlético Madrid’s Primera Liga triumph last season bucked the trend of a decade in which the league title was a binary affair whose trophy’s destiny rested only with Barcelona or Real. This kind of dependable success at both clubs is, as will be demonstrated below, bankable.

There are two anomalies in the table above, however. The first is Paris Saint-Germain, who were nominally European football’s highest commercial earners in 2012-13. This is because most of their income has been derived from Qatar-related entities following the takeover of the club by the Qatari sovereign-wealth fund. Similarly most of the top-line sponsors of Manchester City derive from regional interests. This took commercial income that totalled £18.9 million (€23.8 million, $29.6 million) in 2007, the year before the takeover by the Abu Dhabi United Group, to £166.9 million in 2012-13.

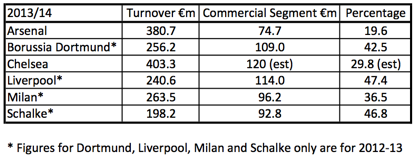

Shareholders of other major European football clubs might be excused for knocking on the door of the chief commercial officer and asking angrily why they have not achieved similar incomes from their sponsorship offerings to Barça, Bayern, Real and United. Because it is clear they have not: when analysing figures from other major European football brands a distinct second tier of clubs emerges.

European football’s seventh- to 12th-highest commercial incomes

But there is good reason why this should be, and however persuasive a salesman the CCO is, the chances of closing the gap on the most successful clubs are probably slimmer than those of Ludogorets winning this season’s Champions League. And here is why.

Manchester United in particular have made great commercial hay by targeting the market leader in geographical regions and industrial sectors for sponsorship tie-ups. This has brought crisp-manufacturer partners, marine-diesel partners, tire partners and noodle partners in various regions, mostly in Asia. Far from cheapening the brand, as many involved in commercial sales in football thought it might, there has been a virtuous circle instead.

United’s brand presence among market leaders who have the rights to use the club’s marques is ubiquitous. Marketing officers at other leading regional firms in different sectors have seen the effect this has on sales and have sought their own associations. This has permitted United to charge premium prices for such associations, such as the £750 million (€945.9 million, $1.173 billion), 10-year deal with Adidas for their kit supply, beginning next season.

But this has been possible only because United can trade on a track record of success. Since its inception in 1992-3 there have been 22 completed seasons in the English Premier League, United having won 13 of them. This reliability is what sponsors want, and whatever the attractions of history – or Wenger’s pretty patterns and Champions League consolation prize – there is no premium to be paid for it. The success here and now that will sell sponsors’ products in the future is what matters.

Indeed, being an also-ran on the pitch has a doubly limiting impact. Clubs who have sought to expand their overseas operations have found themselves chasing the same sponsors, sometimes on the same day. I have heard tales about how the sales representatives of three major English clubs have all pitched up at the offices of a leading company in the Far East at the same time on the same day. All have made their sales presentations, all with variations on the same theme of association with historical success – and all have been met with the same, impassive expression from the sponsorship buyer across the table. The outcome has inevitably led to the clubs who set out for multimillion-pound returns from their sponsorship-licensing property undercutting each other in a race to the bottom just to get a deal over the line, however small the returns.

Clearly the sponsorship buyer who instructs all three much-of-a-muchness clubs to come to his office at the same time on the same day has played an absolute worldie blinder for his firm. But there is a lesson here for those on the football side of the table too, and it seems some clubs have learnt it. Expansion of satellite offices into local markets chasing sponsorship dollars brings out the law of diminishing returns for those who cannot match their commercial aspirations with success on the pitch. Every euro cent spent on offices in Asia or America reduces the margin on what is already a very limited return on investment due to the second- and third-tier clubs’ sponsorship properties being a buyer’s market. And every penny drawn away from the core activity of winning football matches must be counted very carefully.

Similarly, though, those at the top must also be very wary of the threats from below. Manchester United’s experience last season, when they failed even to qualify for the Champions League in the first season after the retirement of their most-successful manager, Sir Alex Ferguson, is a salutary tale. With Chelsea looking dominant with a young team under Jose Mourinho, it might signal a still-longer period of trophy-parched wilderness for England’s most-decorated club. Then the premium that United charge for their commercial licensing might last only as long as the current cycle of contracts have to run.

For in football, both on and off the pitch, there can be only one winner.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at [email protected]om.