“Greek football is a labyrinth.” Petros Konstantineas MP, ex-FIFA referee

Fearsome though the bull-headed Minotaur was, at least Theseus knew what he was dealing with. And if things got too hairy he could always follow the thread of Ariadne’s wool he had laid down on his way into the labyrinth’s heart of darkness. For the modern-day Greek heroes like Petros Konstantineas, the referee who bravely sought to tackle the beast in whose clutches football in that country is held, the enemy is all the more dangerous and insidious. It is a nameless, faceless System, which, despite operating from dark shadows and taking great care to cover its tracks, can still strike with all the power and penetration of a sharp-horned bull.

I learned as much in my many conversations with the honest journalists, referees, club owners and staff I spoke to while investigating the scandal in Greece last week. [See related articles below.] Their accounts of the situation are dismaying for anyone who loves the game of football. But it is also a cautionary tale for all leagues in European football.

It may not number among the top five nations in Europe but Greece is no football backwater. It is ranked 12th in Europe by coefficient, meaning the national champions gain direct access to the Champions League. Panathinaikos have reached as many European Cup finals as Arsenal. Olympiacos last season only narrowly lost in the round of 16 to Manchester United after winning the home tie 2-0.

Yet the game there has been subverted by a culture of match-fixing aimed at making ends meet for cash-strapped clubs tapping in to the betting markets. Those who might have blown the lid on it have been kept sweet by bribes. Those who cannot be bought off are threatened or, worse, assaulted. Worse still, at least one – Konstantineas – has been the victim of a bombing.

As the journalist Thanos Blounas told me in a story others corroborate, the bad smell around Greek football began late in the last century, when elections to the Hellenic Football Federation board took place. An investigation into alleged bribe-taking in the vote proved inconclusive but many observers were sure that the system that allowed fewer than 60 regional councillors to vote for 15 key boardroom posts – obtained with a simple majority of 30 – was open to abuse.

It is said that a graft fund of $1m was enough to secure the passage of favoured candidates and with it control of the refereeing and football-disciplinary systems. The threats began early in the life of The System. Elector councillors were each given two different people to vote for: one would be the candidate The System wanted to see voted in. The other would be a candidate unique to the councillor. If that candidate did not receive his vote then those pulling The System’s strings would know the councillor had reneged on a promise, prompting reprisals.

Attempts by the government to reform the HFF began as early as 2006, under the sports minister George Orfanos. But the HFF called in UEFA and FIFA and the government was spooked. Amendments to his bill meant it lurched into a new direction: rather than limit the HFF’s powers it recklessly extended them, permitting it complete statutory autonomy in all football matters. Rightly, given what it has led to in the intervening decade, UEFA has reportedly consented to that element of the 2006 Sports Act being repealed.

(This, if indeed true – since there has been no official statement from Nyon as yet – is a thoroughly welcome move. Were it not to act to facilitate the Greek government’s attempts to purge Greek football’s Augean Stables, then questions over an apparent obstructiveness would be legitimate. Especially since it must surely be aware of what has been going on in Athens, what with UEFA’s deputy general secretary, Theodore Theodoridis, having been an HFF board member from 1997 through to 2008 and all.)

After that 2006 Sports Act, there ensued a period where clubs yo-yoed around the four leagues due not to their performance on the pitch but to regulatory interventionism. Punishments were meted and reduced; meanwhile league sizes expanded and contracted like the accordions favoured by so many Greek musicians as clubs with connections sought to bypass the onerous process of football promotion by pulling strings.

All the while, the culture of match manipulation grew stronger as certain club officials pulled other levers with refereeing chiefs, match officials and compliant opponents. With the HFF introducing a rule requiring proof of the involvement of fully three players before a match would be considered fixed – a preposterous threshold that makes anti-corruption efforts fruitless – enforcement simply did not exist. It was a cheats’ charter.

The influx of internet betting has only made the situation more dangerous. As the chief executive of AEK Athens, told me: “From the moment Greece becomes more and more poor the people who came around Greek football were people around betting.”

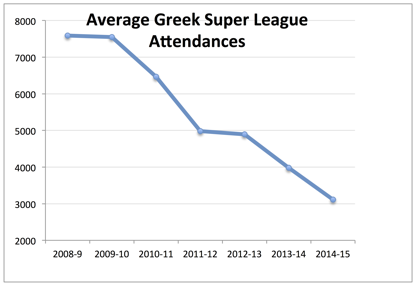

Match results were as scripted as the endings of Aeschylus’s plays, bringing about a situation that was no less tragic. Fans soon began to switch off, as the following chart shows.

In only six seasons the average gate at Greek Super League matches has collapsed by 59%. Consequently, clubs’ revenues fall similarly hard leading to a self-reinforcing cycle of financial distress that leads to desperate measures to protect what little income can be generated. With anything but effective regulatory oversight from the HFF, corruption is truly killing the world’s most beloved sport in a nation where so many clubs were founded as far back as the 1890s – 125 years ago.

It is tempting, at a time when so many negative headlines are written about the Greek economy at large, to consider this a symptom of a uniquely Greek disease. After all, in its first-ever report into corruption in the 28-member Eurozone, the European Union revealed that in Greece very nearly all companies regard corruption to be widespread. But so too did almost all companies in Spain and Italy. Corruption is far from being a uniquely Greek phenomenon.

As Transparency International’s Carl Dolan said at the time of the EU report: “Europe’s problem is not so much with small bribes on the whole,” Transparency International’s Carl Dolan said. “It’s with the ties between the political class and industry.

“There has been a failure to regulate politicians’ conflicts of interest in dealing with business. The rewards for favouring companies, in allocating contracts or making changes to legislation, are positions in the private sector when they have left office, rather than a bribe.”

The same applies in football, where close relationships the regulators in the leagues and national associations have with clubs can at times seem inappropriate. Back scratching might seem at the time a cosy and expedient path, especially when favours are mutual. But in the end, good governance – the only true path for the guaranteed health of football – requires a level playing field for everyone, meaning the dispassionate and consistent applications of reasonable rules at all times.

Because if not, it is a slippery slope to Greece and its Super League, a moral maze from which no ball of wool can show the way out.

Related articles:

http://bit.ly/1DEssYq and

http://bit.ly/1GTEUe9

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745390654labto1745390654ofdlr1745390654owedi1745390654sni@t1745390654tocs.1745390654ttam1745390654.