When Newcastle last won the English top-division title, they really did do it in black and white. It was 88 years ago. It is 60 years now since Newcastle last won the FA Cup and 16 since they lost the second of two consecutive finals. In short, theirs is not a tradition of trophy-laden triumph.

Indeed, apart from the 1950s, since the Second World War Newcastle have spent at least one season outside of England’s top division in every decade. They have been a regular, but not permanent, fixture on the Premier League fixtures list.

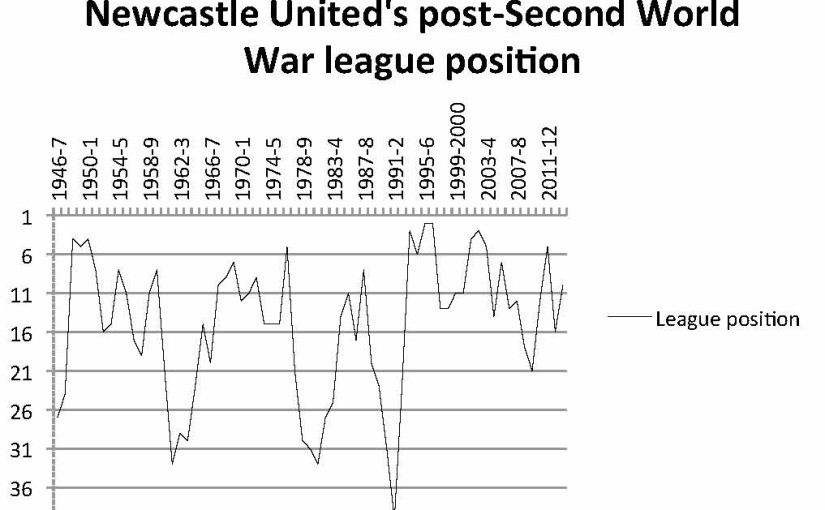

Take a look at the chart below, showing Newcastle’s historical finishing position in the English-football pyramid since 1946-7. As you can see, it has all the pulsing volatility of a cardiogram.

So to break it down: Newcastle spent 15 of the 67 completed seasons outside of the top division – or 22% of them. In all that time they did not win the title once and only spent 21 seasons in the top 10 of English football – or 31% of them. They had a mean finishing position over the period of 15.85 – substantially closer to 16th than 15th – and there is a standard deviation of 9.03, implying the volatility we can see over time.

Mike Ashley took over as Newcastle owner in the summer of 2007, shortly before the financial crisis struck. In his seven completed seasons, the average finishing position has been 13.43 (s=1, implying quite considerable consistency in this, the current season’s relegation scare notwithstanding).

Depending on what happens in the final round of Premier League games in the coming weekend, when Newcastle host West Ham United at St James’ Park to secure their Premier League safety, they will either be relegated to the second tier during this decade, as they have been in so many others, or they will survive. But whatever happens, it will not be an unusual campaign for the Magpies given their historical record.

Even so, the supporters are restive. Their arguments are best articulated by the website AshleyOut.com, which describes Ashley’s tenure as “an organised tumble into mediocrity”. Some of what the website has to say is unarguable. “There have been embarrassing appointments at director and managerial level, our club and ground have been associated with tacky brands [and] club legends have been humiliated.”

On each of these points there is a valid example. Appointing Joe Kinnear, a former heart-attack victim with a genuine dislike for most journalists, was never going to be a public-relations success. Several foul-mouthed tirades and another heart attack later and Kinnear was gone from Newcastle. Bringing in Wonga.com as title sponsor, a firm that was last year banned from using a television advert that declined to make public to consumers its 5,853% annual interest bill, was never going to win hearts and minds either.

And Ashley’s cohorts should probably have thought through the consequences of upsetting Kevin Keegan, whom the club’s own website introduced as a “Geordie messiah” upon his return for a second, unsuccessful spell as manager. These, it must be said, are all fair points but none of them is a crime against football, or unique to Newcastle.

But then AshleyOut.com goes on to make some completely spurious accusations that have little basis in fact. “Club debt has risen, match day and commercial revenue have dropped significantly and, most importantly, our league and cup records have deteriorated,” it adds.

Newcastle’s net debt is £94.9 million, which is nominally higher than before Ashley took over. But the claim is also disingenuous. There are £18 million of loans that are repayable on demand and £110 million of longer-term loans, all offset by £34.1 million of cash in the bank. However, what AshleyOut.com omits to mention is that all of these loans are owed to Ashley himself and they do not bear a penny in interest.

While not mentioning this pretty-damn-important fact, it also overlooks what the financial picture was in the penultimate 12 months of the previous regime’s stewardship of Newcastle, and it was far from pretty. The club was drawing £5.5 million against an overdraft and had £64.9 million of loans with institutions. These bore a crippling coupon that cost them £5.635 million in interest alone, or 6.5p in every pound Newcastle earned. When diverted to the playing squad, that interest bill could have paid for two players each earning £50,000 a week – which in 2005-6 Premier League terms was a huge sum of money.

Add in 2005-6 debt repayments of £4.9 million and Newcastle spent more than £10 million in interest and installments over that 12-month period. Only £11.4 million of new borrowings could cover it. In that same season the Magpies paid out £25.7 million on new players, raising the 2006-7 wage bill by £15.2 million, or almost 20%, at a time when turnover had risen only £10.5 million.

This was Newcastle’s halcyon period, when they were routinely competing in European competitions. But it was playing success borrowed from the future. Even before player trading, Newcastle were spending more than they earned. Where they had routinely plugged gaps with new debt, would lenders have handed over the cash after the financial crisis struck? Or would they instead have been forced into the kind of player-asset-selling spiral of decline and relegation, leading to bank foreclosure and administration, as Southampton suffered? We will never know, because Ashley replaced the external debt with his own loans that the club had no need to service annually.

So that hopefully deals with AshleyOut’s club-debt complaint: the club is absolutely without question not financially worse off under him than before. Then there is the issue of match day and commercial revenue. I find it truly puzzling that presumably paid-up Newcastle fans would call for their club to raise match day revenue, which is already some of the highest in the land. In 2006-7 there were 27 home matches, raising total match day receipts of £33.6 million. Last season there were 22 home games, worth £25.6 million in total.

This meant Newcastle were earning £1.24 million per game back then and are taking £1.16 million now. This is a real-terms, post-inflation drop in per-game ticket revenue of almost 25%. With occupancy rates of 95.9% of capacity, it can only be assumed that the decline in gate receipts from 2006-7 to 2013-14 was down to substantial real-terms cuts in ticket prices. What’s the beef?

Newcastle earned £25.6 million of commercial revenue in 2013-14, compared with £27.6 million in 2006-7, which is a 7.25% drop. But the sponsorship landscape has changed unrecognisably in the intervening period. Back then, Newcastle were one of England’s six richest clubs, with a turnover higher than Manchester City’s, comparable with Tottenham Hotspur’s and only a few tens of millions less than Liverpool’s. They were in Europe and had competed in the Champions League within the previous five seasons, adding to their marketability.

But even before Ashley took over, Newcastle’s qualification for the Champions League had become highly improbable with the arrival of Roman Abramovich and his billions at Chelsea. That improbability became as good as impossible with the deployment of Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth at Manchester City and after the financial crisis struck, firms became more discerning about whom they would sponsor. Now, blessed by their boom-town London location, Tottenham generate revenues 50% higher than Newcastle, Liverpool more than double. [See related article below.]

That Newcastle still generate in excess of £25 million a year in sponsorship, retail and merchandising revenue (while Everton take less than half that at £11.8 million despite a much greater history of success) should be a source of pride, not rancour. And if Newcastle do not take sponsorship income from Sports Direct, the FTSE-listed retailer of which he is a substantial shareholder, it is because they do not need to. The club is a wholly owned subsidiary of MASH Holdings, through which Ashley also holds his shares in Sports Direct. If he wants to put money into his club he can do so with his own cash through equity or soft loans, and does not need to put it in through sponsorship revenue.

The fact is Newcastle have not needed his money in recent years. In 2011-12, when they finished fifth, they generated £93.3 million in revenues and, despite a wages-to-turnover ratio of 68.7%, still had £11.9 million left over to spend on transfers – which they duly invested. In 2012-13 there was a £14.3 million operating-cash surplus and a net £17.7 million was spent on players, sending the club £4.5 million into its overdraft. Last season the operating surplus was £25.6 million in cash and a net £8.3 million was generated from the transfer market, producing an overall cash surplus of £31.4 million.

A pretty good indicator of a club’s natural finishing position lies in its wage bill, and Newcastle were one of few of the non-title-aspirant clubs to invest heavily in theirs. While Everton added only £6 million of the £34.1 million in fresh funds they received from the new Premier League television deal in salaries, pushing it down from 73.0% of turnover to 57.5%, Newcastle splurged on theirs. Of the Magpies’ own £34.1 million uplift in revenue, £16.5 million was committed to wages, leaving the ratio at 60.4% of turnover down from 64.4%.

When Newcastle were fifth in late November of this season, that did not seem like bad business, nor was it the “deterioration” in the league performance that AshleyOut.com claims. But what was happening on the pitch was not reflected in the stands. Another website, SackPardew.com, produced 3,000 leaflets in a campaign aimed at driving him from the dugout.

It worked, as Pardew switched clubs (and league positions) with Crystal Palace with John Carver taking only 10 points from a possible 54 after his January 1 appointment. Newcastle fans should hope that if the club goes down, Ashley will support them financially through the Championship again as he did five seasons ago when they bounced back as league winners. Because after the collapse experienced following Pardew’s departure, they should be careful what they wish for. If Ashley pulls the plug on his investment then the spiral of terminal decline they risked entering before he arrived, one experienced by other good clubs such as Leeds United and Portsmouth, could very well become a reality.

Related article: http://bit.ly/1yJ5IHg

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1743626640labto1743626640ofdlr1743626640owedi1743626640sni@t1743626640tocs.1743626640ttam1743626640.