“Sacked in the morning, your getting sacked in the morning…” Terrace chant

It is one of football’s accepted truths that no employee in a club is more important than the manager. His influence on the most decisive input into the club’s operations – the results on the pitch – makes him so. It follows then that with so much swinging on how they do, there must be some objective measure for the quality of their performance.

Yet most hire-and-fire decisions over the dugout are based on emotional factors. Fans can turn against unpopular managers, vocally expressing their upset, and pressure builds on boards to take decisive action. Indeed, the old football axiom is that no manager is ever more than three defeats from the dole queue. But is that fair? Is it even helpful? These are questions that can only be answered by impartial analysis of performance.

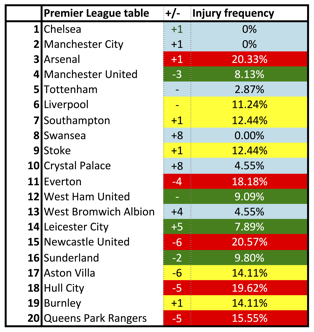

Last week I demonstrated here the impact of injuries on clubs’ activity [see related article below]. There is a reasonable correlation between where a club finishes in the league and the estimated value of their playing squad. But when injuries are factored in, the correlation becomes almost perfect, as the table from last week, represented again below, shows.

If a club suffers medium- or long-term injuries of 60 days or more to first-choice players (those who have started the previous three games), these count towards the injury-frequency statistics in the table. With 38 games per season and 11 starters in each game, the number of matches these first-choice players are medium- or long-term absentees can be expressed as a percentage of the season as a whole.

The +/- column in this table shows how far a club deviated from the league-finishing position that was expected of them according to the value of their squad. It is clear that player-injury frequency is in most cases a determinant in clubs’ overall performance.

Impact of player injury on 2014-15 season Premier League table

As explained in last week’s column, those in the pale-blue band have got away with a light extended-injury frequency, the greens have suffered the expected case, those in yellow a heavy case and those in red severe.

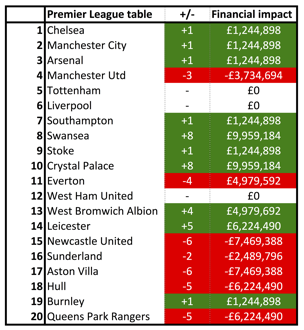

The above table implies a financial impact too. The finishing position achieved is worth a certain sum of money to a club due to the merit payments received from the Premier League. The results are as follows:

This is not small potatoes. For Swansea City, the £10 million extra they earned from their Premier League performance was equivalent to 10.14% of their previous season’s turnover. Had they finished 16th as expected, this substantial bonus would not have come their way. Likewise for Crystal Palace, where their performance bonus was proportionally even more valuable, worth 11.01% of the previous season’s entire revenue base.

But for Palace the impact was still more important. Had they finished according to their 18th-place squad-value projection, they would have been relegated. It follows that this season’s Premier League revenues have also become available as a result of Palace’s improved on-pitch performance. The difference between finishing 20th in the Premier League in 2013-14, a season in the same three-year broadcast cycle as the current and last ones, and a first-season parachute payment in the Championship was £35.9 million. So it is reasonable to say that Palace are £45.9 million better off as a result of their strong results on the field.

Where this information is of particular value is in assessing the quality of a manager’s performance. How has he fared when confronted with injury? Has he raised his team above where they would be expected to finish according to the value of their squad? Have they underachieved against the resources at his disposal?

This requires deeper analysis. The simple reference to how many league places a club has risen or fallen versus expectation does not suffice. This is because all teams are not made equal: to consider that Burnley has the resources of Manchester United, just because they played in the same league, would be preposterous.

So what I have done is to combine the relative resources of each club with the injuries they suffered during the 2014-15 season and come up with a coefficient for each manager according to the specific circumstances they faced. Jose Mourinho was garlanded with his third Barclays Manager of the Season award last season, but does that stand up to objective scrutiny?

Well, actually, no. Given the serene lack of injuries he suffered in what was already a very well-resourced squad, Mourinho should have won the league in any case, and fairly comfortably. Indeed, the effort to which Chelsea players went to win the league last season appears to have placed strain on their performances this year, so there is an argument that Mourinho did worse than might have been demanded of him. However, that is merely an opinion and this study is about objective analysis, so I’ll leave that thought with you.

Manchester United’s performance was impacted by injury but even in the injury-adjusted measure they should still have finished second, ahead of Manchester City by a point or two. Instead they came fourth. The fact they did not do better is testament to Arsenal, who massively outperformed in the face of super-severe injury problems to first teamers.

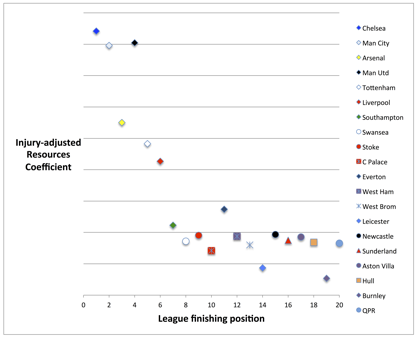

As a whole, the relative performances of each Premier League club can be illustrated with the following scatter graph. The closer to the left of the chart, the higher up the Premier League table each club finished; the higher from the bottom of the chart, the better the injury-adjusted resources available to each club through the course of the season.

It is

It is

It is clear from the graph that even after injuries there was a fairly even spread of resources available to the managers of Queens Park Rangers, Hull City, Aston Villa, Sunderland, Newcastle, West Bromwich Albion, West Ham United, Stoke City and Swansea City. Injuries, as they say, were a leveller for the richer clubs in that bunch. However none of them had anything like the resources Chelsea, Manchester City and Manchester United had at their disposal.

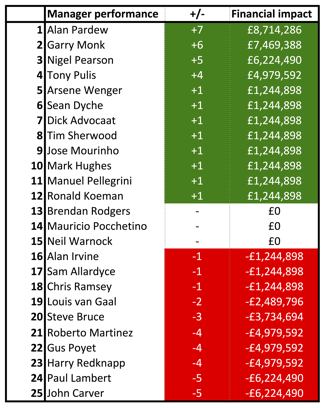

This is where the manager’s skill comes in. A manager with reduced resources available through the course of the season who forces his club further up the league will have been of more value to his club than one who underperforms against availability. It is possible to rank the managers’ performances from the available data. Indeed, this also can be expressed in financial terms, as depicted in the following table.

What the table shows is that with the right man, a change of manager can be effective. Aston Villa under Paul Lambert, West Bromwich Albion under Alan Irvine, Crystal Palace under Neil Warnock and Sunderland under Gus Poyet were all in grave danger of relegation when their boards pulled the trigger. And although this is a far-from-scientific hypothesis, since the sample size is so small, it does seem from last season’s evidence at least that when choosing a new manager mid-season it is necessary to look outside the club.

The appointments of John Carver at Newcastle United and Chris Ramsey at Queen’s Park Rangers – both of whom had been associated with previous regimes – oversaw a worsening of form at their respective clubs. What had been a points per game return of 0.826 under Harry Redknapp – which, for the avoidance of doubt, would still have left QPR bottom if it had gone on all season long – became 0.733 under Ramsey.

But it was Carver who was quite comfortably the worst performer in the Premier League. The excitement and drama of the final-day survival notwithstanding, Carver’s 0.684 points per game was abominable for a club of Newcastle United’s strength. Indeed, even the fact he was missing Paul Dummett, Cheik Tioté, Steven Taylor and Massadio Haidara for lengthy spells of the campaign should provide little excuse. Alan Pardew had lacked Gabriel Obertan, Jonas Gutiérrez, Ryan Taylor and Siem de Jong, but when he left the club on New Year’s Eve 2014 they were only one place below where they would otherwise have expected to be. More on Pardew shortly.

Redknapp had lost Alejandro Faurlin for the season in game three at QPR. But again my coefficient shows that both he and Ramsey should have done better considering the value of the resources they still had at their disposal.

Likewise Steve Bruce also had some rotten luck with injuries, not least that his star signing, Robert Snodgrass, suffered a season-ending breakdown in his very first outing for Hull. This is what took Hull down, but even so the coefficient shows Bruce was unable to make the most of what he had left.

Louis van Gaal declared himself pleased with how things went last season but, even when adjusting for the injuries to Michael Carrick, Jonny Evans and Jesse Lingard, Manchester United’s performance under him was a letdown. By contrast to these outcomes were the rather-better showings of Sean Dyche and Arsène Wenger. Both Burnley and Arsenal overcame bad injury difficulties to overhaul teams with far deeper pockets.

But even they were not the league’s best performers. Those laurels belong to Nigel Pearson at Leicester City, Swansea City’s Garry Monk and Pardew, at Crystal Palace in particular. Those three generated multimillion-pound performance bonuses for their teams, lifting them substantially above their expected positions once injury records were taken into account.

Now what this study cannot control for is emotional factors. Things like the “12th man” effect of the incredible fans’ atmosphere at Leicester’s King Power Stadium, or how a gilded dressing room like that at Old Trafford would react to another new man so soon after Sir Alex Ferguson’s triumphant march out of Manchester United. So perhaps there are positive or negative inputs out of a manager’s control that are impossible to quantify here. Nor is it comprehensive for due diligence purposes, since it cannot reveal any personal issues particular managers might have. But what it does do is provide a dispassionate, scientific analysis of managerial performance that could and probably should serve as the foundation for decision-making in this most important of strategic appointments at the modern football club.

Now who should be most encouraged by the results here? Well it is of course good for the clubs who have the top-performing managers. But it is surely best for the Football Association. For the common denominator between the top-three performing Premier League managers last season is that they all are English.

If the serving England manager, Roy Hodgson, should be sacked in the morning – or, more likely, should his contract peter out after another disappointing international tournament – the FA should consider the results here. Because although the top people there might rail against the number of English players in the Premier League, they should be cheered by the quality of its English managers.

Related article: http://www.insideworldfootball.com/matt-scott/17828-matt-scott-injuries-will-drag-you-down-it-is-not-a-question-of-if-but-when

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at oc.ll1745643332abtoo1745643332fdlro1745643332wedis1745643332ni@tt1745643332ocs.t1745643332tam1745643332m.