“We dare not tempt them with weakness. For only when our arms are sufficient beyond doubt can we be certain beyond doubt that they will never be employed.” John F Kennedy

Strategy for both the Eastern bloc and the NATO allies during the Cold War was simple: arm yourselves to the teeth until the threat of Mutually Assured Destruction guaranteed neither side would be stupid enough to go to war. Turns out it worked.

Of course in the eternal cycle of football there is never a complete cessation of hostilities, just a pause every close season until a new front is opened. Yet our game certainly has an arms race, and the perception of who is winning it influences results on the pitch.

When Chelsea began the 2014/15 season bolstered with Cesc Fábregas and Diego Costa, inter alia, Jose Mourinho knew what it meant. “From my perspective as Chelsea manager, I say ‘We want to be champions, we’re ready to be champions, and we’re not looking at other teams.’ I have the squad I want and the right profile of squad to attack the title.”

This confidence infused his squad and, with 32 points from their first 12 matches – including trips to the Etihad Stadium, Old Trafford and Anfield – the foundation for winning that title was quickly built.

Ditto Manchester City this season, with Raheem Sterling, Kevin De Bruyne and Nicolás Otamendi joining an already robust squad, the first five games produced five successive wins. Media and pundits everywhere had crowned City champions before September was out, which complicates the psychology of lesser players who face them. The old sporting axiom about losing the match in the tunnel begins to ring true.

As such, in football at the top end it is important to participate in the transfer-market arms race. Being seen to strengthen simultaneously raises the self-belief in the dressing room and unsettles the opposition. By the same token, losing the best players in a squad can have a commensurately negative effect.

When Arsenal began the 2012-13 season shorn of Robin van Persie and Alex Song, after 15 games they were 10th, having dropped 24 points. They were not in fact as bad as all that – from their last 15 matches they dropped only nine points. This is the context in which Liverpool have toiled in recent seasons and it is the context in which Brendan Rodgers has this week lost his job as their manager.

Liverpool are currently 10th in the Premier League, six points off the title pace, following defeats to Manchester United and West Ham United and a succession of perhaps-unexpected draws. Football is a results business and Rodgers has evidently not achieved the level expected of him.

After the heady heights of 2013-14, when the fateful slip by Steven Gerrard in the pivotal 36th match against Chelsea ended an 11-match winning sequence and Liverpool’s title hopes, the 2014-15 season and the start to this one have been for Liverpool crashing disappointments. But are the expectations of the club’s owners and fans fair?

This season began without Raheem Sterling, who demanded to leave the club and found himself a £50 million road to Manchester City. Last season began without Luís Suárez, the talisman of the previous campaign, and they were 12th after 12 games as their new vulnerability was exposed. This, as explained above, is consistent with the early-season experiences of other clubs who have lost out in football’s summer arms race to teams with bigger war chests.

Yet even so, in early April that season Liverpool were still looking good for a Champions League place. It was only after injuries to first-teamers Daniel Sturridge and Mamadou Sakho that belief and form suffered and they slipped to sixth by the season’s end. (For a deeper understanding of why injuries matter in a club’s season, please take a look at the two related articles below.)

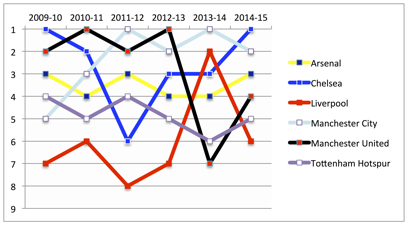

Big 6 Premier League clubs’ finishing positions, 2009-10 to 2014-15

Such details should not be overlooked when assessing Rodgers’s record at Anfield. There should also be consideration of Liverpool’s longer-term past. In the 25 completed seasons since the last time Liverpool won the English league title, their average finishing position has been 4.56. Under Rodgers, with a seventh, a second and a sixth, it has been 5th.

Now it is important to note that comparison of Liverpool today with that of Liverpool at the start of the Premier League era is not like for like. In 1992-93 Liverpool were the third-richest club in England, with an annual turnover of £17.5 million. Manchester United’s was £25.2 million and – this is bound to come as a surprise to you – Tottenham’s was £25.3 million. Back then Liverpool could compete for whomever they wanted in the transfer market and, for the right terms, top players would willingly sign, though history shows they seldom invested well.

Today, as the departures of Sterling and Suárez demonstrate, Liverpool are far from a dream destination. The reason for this is financial, as the table below illustrates.

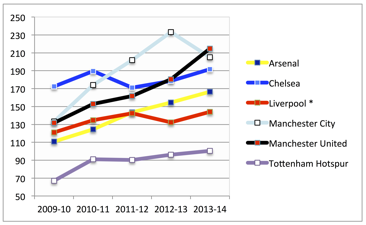

Big 6 Premier League clubs’ wage bills, 2009-10 to 2014-15

* NB: For 2011-12, Liverpool’s reported accounts were for a 10-month period only. Their wage bill has been annualised according to reported 10-month figures.

In June 2010, four months before Fenway Sports Group [FSG] took over Liverpool, their wages were highly competitive, about £12 million less than the two Manchester clubs were paying and about £10 millio more than Arsenal. Yet in the intervening years Rodgers has been the key figure in a period of managed decline.

While the compound annual growth rate [CAGR] of Arsenal’s wages was 8.49%, City’s 8.99% and United’s 10.27%, Liverpool’s was only 3.54%, allowing a gap to open up and widen under FSG. Although the picture is not as pronounced in terms of football investment (the net amount spent on player transfers and wages combined) there is again evidence of managed decline.

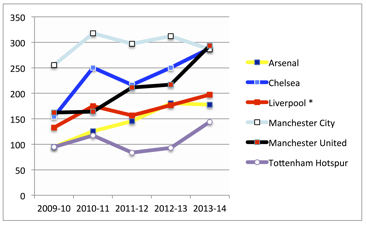

Big 6 Premier League clubs’ football investment, 2009-10 to 2014-15

* NB: For 2011-12, Liverpool’s reported accounts were for a 10-month period only. Their wage bill has been annualised according to reported 10-month figures.

The CAGR trendline in football investment for Chelsea, Arsenal and United has been sharply upwards since the 2009-10 season: 13.31%, 13.36% and 12.61% respectively for those three clubs. At Liverpool the trend has been less positive, at only 8.23% CAGR. In 2013-14 there were three clubs with football investment of close to £300 million a year. Liverpool’s was, at less than £200 million, a long way behind.

Indeed, the period under review (that for which clubs’ audited financial data are publicly available) does not include analysis of the summer-trading windows before the 2014-15 and 2015-16 seasons. It is fair to assume that with Suárez and Sterling departing, for club-record and English-record fees respectively, Liverpool’s history of £50m-plus net-transfer-market investment may be behind them.

Here is why losing Rodgers is a big risk for Liverpool. A man who started well enough to have established a long-term tenure at one of the biggest brands in English football has now been lost. This comes at a time when they will probably be forced to divert transfer-market funds into developing new stands at Anfield.

Currently they have the fifth-biggest stadium in England. They have the fifth-biggest wage bill. According to Transfermarkt.com estimates, they have the fifth-most-valuable squad. To expect them to finish anywhere above fifth is for the fans and the owners something of a conceit.

Whomever they now approach to replace Rodgers will no doubt seek assurances about a change in financial strategy. The highly popular former Borussia Dortmund coach Jürgen Klopp would surely not head to Anfield without some guarantees about transfer-market flexibility. Because men of his reputation are seldom tempted by weakness.

Related articles:

1. Injuries will drag you down. It is not a question of if, but when

http://www.insideworldfootball.com/matt-scott/17828-matt-scott-injuries-will-drag-you-down-it-is-not-a-question-of-if-but-when

2. Managers are too important to hire and fire on a whim. But are they all up to it?

http://www.insideworldfootball.com/matt-scott/17892-matt-scott-managers-are-too-important-to-hire-and-fire-on-a-whim-but-are-they-all-up-to-it

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745575805labto1745575805ofdlr1745575805owedi1745575805sni@t1745575805tocs.1745575805ttam1745575805.