“We must avoid the impulse to live only for today, plundering for our own ease and convenience the precious resources of tomorrow.” Dwight D Eisenhower

As the Supreme Commander of the allies’ war effort in the European theatre during World War Two who went on to become president, ‘Ike’ knew a bit about budgets. He was fortunate as the 34th President of the US to lead the world’s biggest economy during rampant boom time, a period when median incomes almost doubled for US citizens.

After a biting recession in 1951 and 1952, Eisenhower was in office between 1953 and 1961, when nigh-on double-digit growth rates became the norm. It was an era of such spectacular development for all major global economies that it has since been termed the Golden Age. Yet still Eisenhower recognised the need to check profligacy for the future. What would he have thought of Manchester United’s £75 million for Romelu Lukaku? Or of the £65 million Chelsea have paid for Alvaro Morata?

Personally, I have my views. It is hard, perhaps, to identify when you are in the midst of them the periods of booming economic success such as Eisenhower’s. This is because people tend to expect more of the same tomorrow. (In investment this is termed “recency bias”.) However, given the rate of growth in Premier League incomes, and since another old axiom of investment is that nothing can grow forever, it seems fair to assume that this will one day be looked back on as a Golden Age for English football.

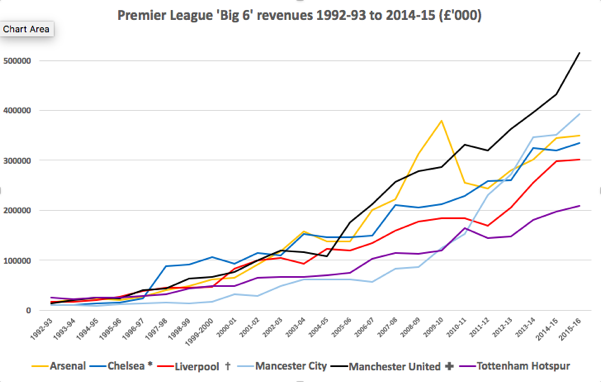

Below is a chart depicting the revenues of the so-called ‘Big Six’ Premier League clubs since the launch of the competition in 1992.

| * Chelsea turnover unavailable for 1992-93 only |

| ✝Liverpool turnover is for 10-month period for 2009-10 only |

| ✚Manchester United turnover is for a 14-month period for 2005-06 only and for 11 months for 2004-05 only |

Over the 24-year period, turnovers for the ‘Big Six’ Premier League clubs have risen at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14.47%. Over that period, UK inflation has run at 2.7%, meaning that in today’s money, the £82.1million they were turning over in 1992-3 would be worth £156. million today. This means that even adjusting for inflation, for those six clubs, growth has run at 11.45% continuously for almost 2½ decades. Globalisation has clearly been very good for Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United and Tottenham Hotspur.

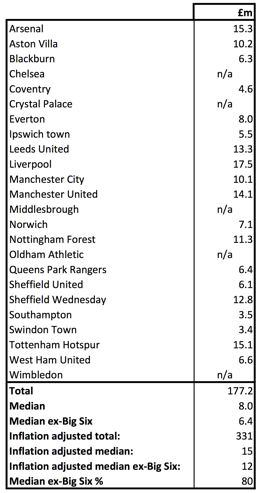

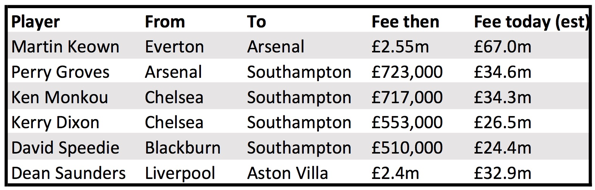

But what is good for the top English clubs tends to be good for the Premier League at large. The competition has witnessed remarkable growth in revenues across the piece. I have collated the revenue data for the 24 Premier League clubs who were involved in the competition’s first season, 1992-3. Only 19 are available, since Middlesbrough’s, Wimbledon’s and Oldham Athletic’s accounts were not published and Crystal Palace and Chelsea’s were withheld.

What we see is that between them these 19 clubs generated an aggregate £177.2 million over the course of the season, equivalent to a median of £8 million each (or £15 million when adjusted for inflation). This means that, even allowing for inflation, Jose Mourinho alone reportedly earns £1.4 million a year more than the entire annual turnover of the average Premier League club in 1992-3.

The reason why Mourinho – and the players under him – are able to earn such fabulous sums is that Premier League clubs’ revenues have grown so astronomically. And it has not been the preserve of the Big Six, either. Indeed, when we look at the median income of the ‘other’ Premier League clubs as a proportion of the total including the Big Six both today and 24 seasons ago, we see that the proportional share of the cake taken by the ‘rest’ is greater than it was in the beginning of the Premier League era.

Then, the median Premier League club revenue without the Big Six (ex-Chelsea, whose turnover was not disclosed) was £6.4 million. With them, the median was fully 25% higher at £8 million. Spool forward to 2015-16, the year for which figures are most recently available, and the full-League median income is only 17% higher than the median without the Big Six.

Take a look at the two tables below, which demonstrate the relative change in revenue values over the 24-season period.

Table 1: Premier League club turnover, 1992-3 Table 2: Premier League club turnover, 2015-16

What you see above matters for a couple of reasons. First, it suggests that despite the vast wealth of the richest clubs, the revenue distribution, a key input in ensuring competitive balance between clubs, is not wildly different to how it was at the League’s inception. Back in 1992-3, Swindon Town were the lowest-earning club for whom figures are available, with a turnover of £3.4 million. This compared to Liverpool’s £17.5 million, a high-to-low multiple of 5.15. In 2015-16, Manchester United were staggeringly generating more than half a billion pounds a year (more than any other club in the world, according to the Deloitte Football Money League), yet that is still only a multiple of 5.86 versus Bournemouth’s in the same season. Indeed, with the new TV deal raising broadcast incomes – the largest element of the bulk of clubs’ overall revenues – by fully 50% from the current season, that balance is very likely to improve still further.

The second reason is that there has been a lot of talk lately about the costs involved in player transfers. First was Daniel Levy, the Tottenham Hotspur chairman and co-owner, talking at a rare public appearance to ring the bell at the Nasdaq stock exchange on Tuesday that he used to deride the expenditure of his Premier League rivals. “I think some of the activity that’s going on at the moment is just impossible to be sustainable,” said Levy.

This chimed with commentary from Mourinho. “Some clubs are paying or they don’t buy because they don’t accept the numbers that are now ruling the market, or to do it they have to go [to] the same levels and for me that’s what worries me a little bit because now we speak about £30 million, £40 million, £50 million in such an easy way,” said the United manager. Even Pep Guardiola, whose bosses at Manchester City have written more £50 million cheques than anyone else this summer, agreed. “It’s a lot,” he said. “Maybe one day it’s going to stop, we will see. I could not imagine two or three years ago that people would pay £100 million or £120 million for one player. Now it’s happened and it’s going to happen more.”

It seems they’re all a bit embarrassed by the profligacy of the Premier League. But is it really all that different to how it ever was? Back in 1992-3 the record Premier League signing was the transfer of Roy Keane from Nottingham Forest to Manchester United, coming in at a cool £3.75 million. The value of that transfer was equivalent to 26.6% of United’s entire turnover, meaning that in today’s terms the record Premier League transfer might be £137 million. It isn’t. And it is not as if the “£30m, £40m, £50m” of today’s transfers is all that outlandish either in a historical context.

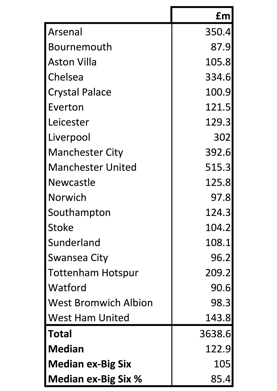

Back in 1992-3, the centre-back Martin Keown joined Arsenal for £2.55 million, a sixth of their then turnover. In the ‘football money’ equivalency of 2015-16 he’d have been £58.4 million. Southampton signed Perry Groves from Arsenal for £723,000 – more than a fifth of Saints’ then turnover, or £25.7 million in 2015-16. On top of that they spent £717,000 on the centre-back Ken Monkou and £553,000 on the centre-forward Kerry Dixon, both from Chelsea, and £510,000 on David Speedie from Blackburn Rovers. That little lot would have come to £63.2 million in 2015-16 (with £37.5 million of it spent on players over the age of 30). The £2.4 million that was spent on taking Dean Saunders from Liverpool to Aston Villa amounted to an equivalent £24.9 million in the 2015-16 season.

But even these numbers are out of date. Let’s just assume that Premier League commercial and matchday revenues have remained completely flat from 2015-16 (they haven’t) and only the broadcast revenues have grown. Adjusting for the 50% growth in that segment alone, it would revise the values of those players sharply upwards, as follows:

Table 3: Selection of 1992-3 transfers in today’s ‘Football money’

Now as an Arsenal fan and colleague of his on the radio, I like Perry Groves an awful lot, both as a former League Champion with my boyhood club and as a man. But I think even Perry, who never won an England cap and who in his final two seasons at Arsenal had been used principally as an impact substitute, making 12 league starts in his penultimate season and five in his last, would surely agree he would not be worth £34.6 million today.

The point here is that enormous fees for players, relative to the purchasing clubs’ revenues, are nothing new. Indeed, even the wages paid today are in relative terms not exorbitant. Keane has revealed that when he signed for Manchester United £3.75 million he was paid £350,000 a year, an annual salary equivalent to a tenth of his transfer fee, plus or minus a bit. Push that forward to today’s ‘football money’ and it would mean a player costing £50 million earning about £100,000 a week, or £60,000 a week for a player bought for £30 million. When adjusting for reduction in fees relative to club turnovers demonstrated above – a phenomenon probably deriving from the effects of the Bosman ruling in 1995 that shifted the power towards the player – these seem about right for today.

What would a man as prudent as President Eisenhower think of all this? Well, take a look at his record in office. In 1960, a year before he left the White House, US infrastructure investment as a proportion of GDP was double what it is today, as the demands of the space programme and building an interstate road network were met. These programmes improved communications and transportation and drove the growth rates the US enjoyed. Eisenhower was all for investing to accumulate.

Transpose Eisenhower’s example to football and I think it is clear how he would see it. He would surely recognise clubs’ investment in players as spending on their core activity: investment that has contributed to the remarkable growth in clubs’ revenues. Indeed, if Premier League clubs were merely to “live for today” then the revenues they generate would instead be drawn away from them and from the game in dividends paid to club shareholders. I don’t think the fans, or Ike, would approve of that.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745645555labto1745645555ofdlr1745645555owedi1745645555sni@t1745645555tocs.1745645555ttam1745645555