By David Owen

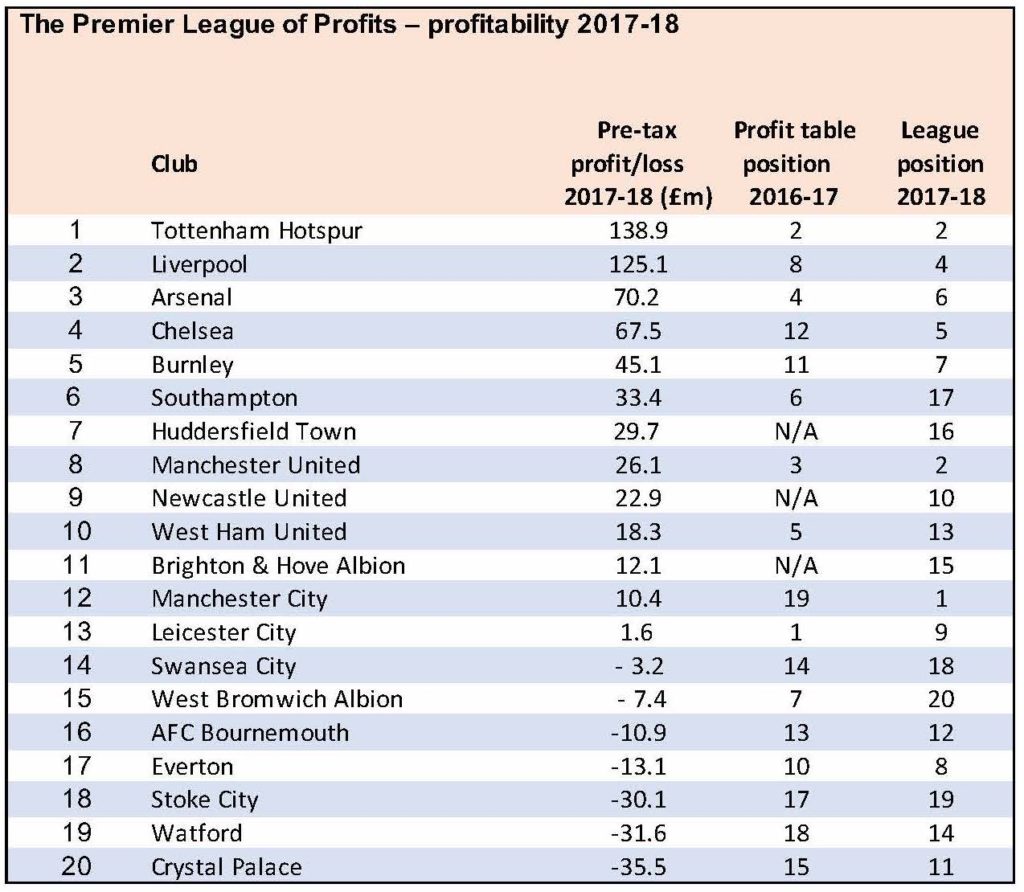

April 23 – The 2017-18 season will go down as the one in which not one but two Premier League teams – Liverpool and then Tottenham Hotspur – set world records for football club profitability. Yet overall, this was only the second-best season ever in profit terms for the 20 clubs who competed in English football’s top flight.

Collectively, the 20 managed almost £470 million – well over £20 million each on average – at the pre-tax level: historically very good, but just over £100 million behind the prior year’s unprecedented total. Moreover, whereas in 2016-17 only one club – relegated Sunderland – reported a loss, this time the figure was back up to seven, including all three – Swansea, Stoke and West Brom – who lost their Premier League status.

So what was going on?

Well, whereas in 2016-17 all clubs had benefited from the large increase in the value of the league’s media rights for the 2016-19 cycle, this time around revenue from this massively important source was essentially flat. This left clubs needing to unearth an alternative source of growth. Broadly, those that did continued to prosper. Those that did not saw profitability decline or vanish altogether as the unrelenting battle to raise standards and ensure survival, or something better, for another season drove up costs.

The main exception to this iron rule were the three promoted clubs – Newcastle, Brighton and Huddersfield – whose turnover received such a boost that cost inflation was never likely to keep pace. This trio accordingly generated nearly £65 million of pre-tax profits between them.

Transfer profits were the most obvious alternative growth source. Amortisation rules allowing the cost of incoming transfers to be spread over the length of a player’s contract make it quite difficult even for comparatively big spenders not to register a profit – as opposed to a cash surplus – on their transfer dealings. Inflation in the market for top talent, the brightest prospects and sometimes just solid Premier League experience has also helped.

Hence the sale of Philippe Coutinho to Barcelona was a big factor in Liverpool’s stellar financial year, even though the Merseysiders did not stint on bringing new talent into the club. Spurs got a boost from transfers too, notably from the sale of wing-back Kyle Walker to Manchester City.

Both of these global profit pace-setters had other things going for them too, however. Liverpool did well out of their run to the European Cup final, where they lost to Real Madrid. Spurs’ growth was enviably broad-based, and the North Londoners also benefit from a wage bill significantly lower than the rest of the Big Six.

With both teams having battled their way to the Champions League semi-finals, where Liverpool can expect to come up against Coutinho, European income should be a big factor in 2018-19 too. Spurs though will have to live for a time with a substantial debt-load, incurred to build their impressive new stadium.

The correlation between financial and on-field performance continues to strengthen, with the five most profitable clubs in 2017-18, including little Burnley, all finishing in the top seven in the league.

Meanwhile, as in 2016-17, the bottom seven in Insideworldfootball’s latest Premier League of Profits listing included only one top-half finisher. This time it was Everton, replacing Manchester City, the champions, who have surged to mid-table mediocrity in profit terms.

Also worthy of note, though less than surprising, is Leicester City’s tumble from the summit of the profits table, to which the Foxes’ on-field exploits of recent seasons had propelled them.

Premier League broadcasting revenue looks set again to be relatively flat in 2018-19, though UEFA income promises to be an even bigger factor for those who have enjoyed successful European campaigns.

Contact the writer of this story at moc.l1752126487labto1752126487ofdlr1752126487owedi1752126487sni@n1752126487ewo.d1752126487ivad1752126487