“Quand on enferme la vérité sous terre, elle s’y amasse, elle y prend une force telle d’explosion, que, le jour où elle éclate, elle fait tout sauter avec elle.” Émile Zola, J’accuse

The French author Émile Zola was the Charles Dickens of his place and time, 19th Century France, and a man for whom the term tour de force could specifically have been coined. His sweeping novels concern themselves with “la vérité” – the truth – chronicling the lived experience of millions of downtrodden French folk whose lives were crushed by their circumstances.

One of his novels, and arguably his greatest, was based around a laundry. In L’Assommoir Zola’s heroine, the hard-working washerwoman Gervaise, eventually succumbs to the brutal reality of her lot. Trying to make her way in life when attached to a violent drunk of a partner proves just too much.

As Zola so pithily observed, if you bury it underground, the truth has a habit of building up to such an extent that when it explodes, it blows everything else up with it. This is axiomatic of any walk of life; even in football. Secrets cannot be hidden, especially if they are hiding in plain sight.

So it has proved for Roman Abramovich, the Chelsea owner. It was always known to be true that the Russian oligarch was a senior apparatchik for a bellicose and kleptocratic regime, but that truth was buried under the ground of Stamford Bridge. There, he was adored by the Chelsea faithful as the big-hearted Santa of SW6.

The truth finally exploded when in February the violent, power-drunk Vladimir Putin, the autocratic president of Russia to whom Abramovich was attached, ordered the illegal invasion of Ukraine. Two days later, the British government declared Abramovich a “person of interest” to the Home Office over what the leader of the opposition, Sir Keir Starmer, alleged under parliamentary privilege to be “corruption”. Soon afterwards, he was sanctioned along with several other senior figures in Putin’s regime.

Chelsea, reigning world and European club champions, had forcibly to be sold. Abramovich’s tenure as owner would come to an end with, so the story went, the orderly passing of the club from his hands to anyone who might be persuaded to pledge £4.5 billion to acquire it.

Surprisingly, the list of suitors was long. A surprise because, despite its prestigious reputation, Chelsea is financially incapable of sustaining itself.

Generally speaking, a football club is much like a household. The money it brings in is its turnover – the household income. For a club this comes from gate receipts, TV money and sponsorship and merchandising.

And just like in your household, where there is a mortgage or rent obligation, utility bills and suchlike, there are certain repeatable bills that must routinely be paid. These are things like player wages, heating and lighting, travel and insurance, that sort of thing. The biggest of these, by far, is invariably the player-wage bill.

Once all that is taken care of, what is left over is known as the operating cashflow. And, as for a household that wants to use its spare cash to splurge on discretionary items like holidays, meals out, cinema or football tickets and whatnot, it is from this that most clubs must find the funds to spend on the one-off things like transfers and stadium improvements.

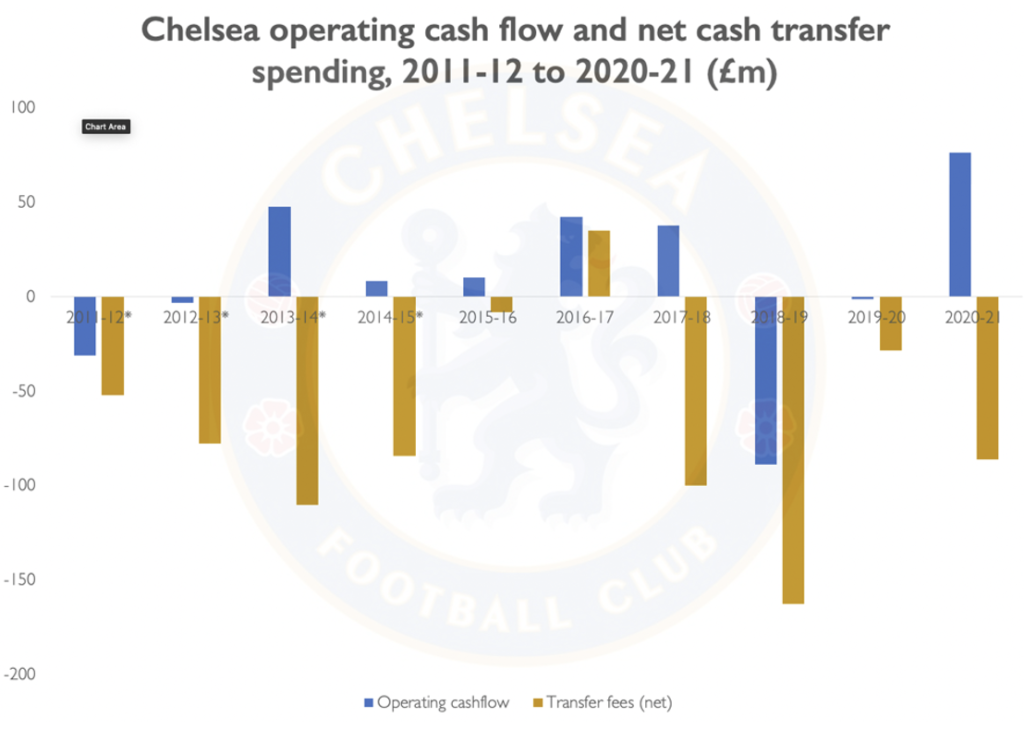

But not for Chelsea. Under Abramovich, they have been one of those rare beasts in football whose sweet tooth has been catered for by a sugar daddy. And then some. Across the past 10 completed seasons, Chelsea have generated a grand total of £98 million in operating cashflow. And yet they have still been afforded the staggering sum of £675.3 million in transfer fees. Net. That is to say: Chelsea have spent £675.3 million more on transfers than they have generated in sales over the past 10 years.

Take away the £98 million in operating cashflow generated over the period and that’s £577 million of transfer activity that’s been covered by loans from the opaque offshore-shell companies apparently controlled by Abramovich (and more on that in a minute).

On top of this there are tens of millions of pounds more that have been spent on stadium and training-ground renovations. And, as can be seen from the table above, most of the £98 million in operating cashflow was generated last year alone, which was highly unusual. The £76.2 million Chelsea hauled in during the 2020-21 season was due in large part to the UEFA prize money received for winning the Champions League.

That kind of lucrative football success simply cannot be guaranteed. Take it away and replace it with Chelsea’s more usual second-round Champions League exits (which they have had in four of the past seven completed seasons) and there is precious little extra with which to fund player purchases after player sales.

Indeed, there have been several seasons when eye-wateringly large subsidies have been required just to meet the operating-cashflow deficit. In 2018-19, a season when there was no Champions League football at all, Chelsea made an operating-cashflow loss of £88.7 million and still found the means to spend £162.5 million in net transfer fees.

A household could not live like this – losing a large slice of the household income and then jetting off for multiple Caribbean holidays. Neither could a football club, generally speaking. It has only been possible for Chelsea to do so due to the exorbitant privilege afforded them by Abramovich.

The terms of the deal endorsed by the UK government stipulated that the new owners must find £4.25 billion – £2.5 billion for the purchase of the club and a further £1.75 billion to invest in the stadium, academy and women’s team. Essentially, a continuation of the exorbitant privilege but in a manner that would invest in revenue-generating infrastructure rather than shiny baubles in the transfer market.

The chances of this happening exploded, though, when another truth was dug up. It had been envisaged that the £2.5 billion would be directed to humanitarian charities supporting the victims of Russia’s illegal war in Ukraine. But that hit a major impasse when it emerged that Abramovich could well seek personal repayment of the £1.6 billion aggregate loans owing to Camberley Investments, a shell company in the secrecy jurisdiction of Jersey that is widely believed to be controlled by Abramovich himself.

See: Abramovich failure to give legal guarantees raises new questions over Chelsea sale

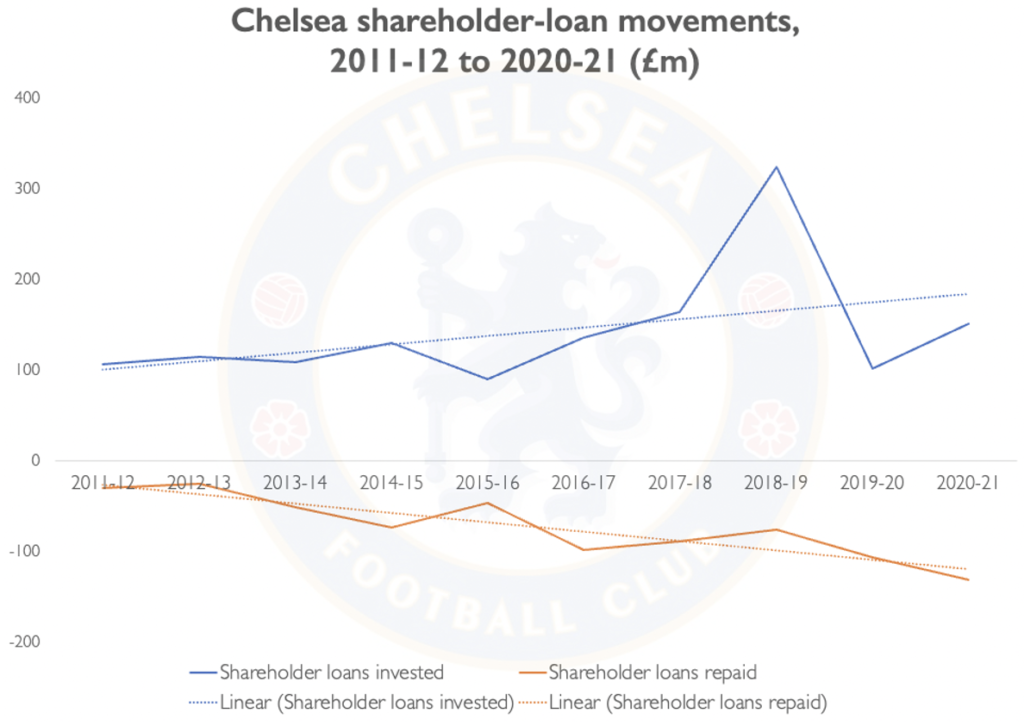

Indeed, it is worth considering how those loans have been run up for a view perhaps as to why the UK government might not wish them to be repaid. In the past 10 years alone, Abramovich has injected £1.425 billion in new loans into Chelsea. And across that same period, fully £729.1 million has been taken out of the club in loan repayments.

Ordinarily, a benefactor-owner would inject loans or equity into a club on a long-term basis, expecting it to operate within that budget for the duration. They might top up the loans as the club outspends its means but would normally only expect repayment upon the club changing hands. At Chelsea, things are different.

There it has been an extraordinary spin cycle of Russian cash in and Premier League and UEFA cash out, consisting of tens of millions of pounds in each direction every single year – both in and out. And, as the dotted trendlines above show, the amounts have dramatically been rising over the period. However, there is no way of proving the purpose of this unusual loan structure from the figures alone, and any attempt to do so is necessarily pure speculation.

It seems, though, that at the same time, law-enforcement authorities have begun to raise concerns about the source of Abramovich’s astronomical wealth. In addition to the UK Home Office’s sanctions having been motivated by perceptions of “corruption”, so too have his activities drawn attention in Switzerland.

Even in his native Russia there had been concerted investigations into his past. A document uncovered by a BBC Panorama documentary earlier this year explicitly stated the belief among economic-crimes investigators that “if Abramovich could be brought to trial he would have faced accusations of fraud… by an organised-criminal group.”

Then, in 2018, when Abramovich applied for a residence permit to live in the Verbier ski resort, he was again the subject of scrutiny. Initially the application was accepted by the local bureaucracy of the Canton Valais. But the Swiss Federal Office of Police (Fedpol) then stepped in and issued a report that alleged criminal activity by Abramovich.

His attorney, Daniel Glasl, said in a statement: “Any suggestion that Mr Abramovich has been involved in money laundering or has contacts with criminal organisations is entirely false. Mr Abramovich has never been charged with participating in money laundering and does not have a criminal record. He has never had, or been alleged to have, connections with criminal organizations (sic)… In fact, FedPol has failed to provide any evidence of criminality whatsoever.”

The truth, despite the sanctions against him? Well, whatever the facts of the matter, if Zola’s lessons are any guide, then it seems Abramovich’s fortunes are intrinsically tied to Putin’s. For Gervaise, things went well for as long as her partner Coupeau could support her. But when he falls from a rooftop and can no longer work, his violent rages consume her, her family and her laundry business.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1741653054labto1741653054ofdlr1741653054owedi1741653054sni@t1741653054tocs.1741653054ttam1741653054