In December 2014 Insideworldfootball columnist Matt Scott wrote the column re-published here. It was somewhat prophetic and shed light on a deep fear facing football at the time. Man City later survived UEFA’s financial interrogation and sanctions following an appeal to CAS. Matt will file a new column on the Premier League charges against the club later this week. Meanwhile the ‘what goes around comes around’ epithet springs to mind. And for Man City it looks to have come around again.

“If you drink from a bottle marked ‘poison’ it is almost certain to disagree with you, sooner or later.” Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

Manchester City’s accounts released last week described a fantastical transformation of their financial fortunes. This is a club truly living in a football wonderland that even the most imaginative Alice of a fan could surely not have dreamed of 15 years ago.

Champions of England and winners of the Capital One Cup, they benefited from the tremendous growth in Premier League broadcasting contracts. Like all Premier League clubs, City have consumed a biscuit marked ‘EAT ME’ that has hugely pumped up their revenues. Uniquely, though, with certain elements of their cost base, the Etihad club have also drunk from the bottle marked ‘DRINK ME’, shrinking things to fit the UEFA financial fair play environment that previously bit them so hard.

It is a remarkable turnaround after City’s comprehensive breach of the FFP regulations in the 2011-12 and 2012-13 seasons led UEFA to impose a €20 million (£15.7m, $24.7m) fine, with a further €40 million (£31.4m, $49.6m) suspended. So let’s see how they’ve achieved it, if indeed they have at all.

Now as I have stated here before it is very difficult to scrutinise a club’s performance vis à vis FFP from the outside. There are a number of elements of a club’s operations, invisible to the external analyst, which are deductible from UEFA’s considerations — such as expenditure on the infrastructure and wages around youth development. This makes accurate analysis impossible.

But it is possible to extrapolate a number of estimates from what the clubs do report, and I shall attempt to do so here. First of all it is worth going over the parameters again, which state that clubs may accumulate a maximum permitted “break-even calculation” loss of €45 million (£35.3m, $55.6m) in seasons 2013-14 and 2014-15.

UEFA’s sums have a number of inputs. On the income side these include general turnover and profit or income from player sales and from the sales of real estate. On the expense side it includes wages, the “other operating expenses” – such as utility bills, agents’ fees, insurances etc.

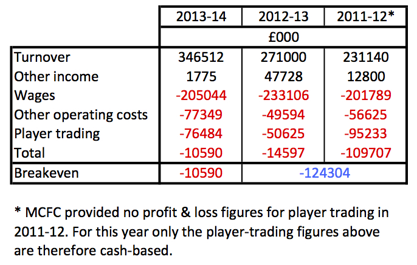

Using City’s reported accounts from the past three seasons, the following picture emerges.

Manchester City income-and-expenses analysis 2012-2014

Here I should reiterate that these numbers are perhaps a few millions out here and there due to the unseen deductibles, but they should be reasonably close to the true state of affairs at the Etihad Stadium. And it is clear for all to see that in the 2011-to-2013 FFP monitoring period, City missed their target as wildly as their woeful former striker Jô ever did with the ball at his feet.

Clubs were permitted cumulative losses over the two-season 2011-2013 period of €45 million. And they absolutely smashed it, although not in a good way. Indeed, the £124.3million (€157.8m, $194.4m) of losses could even be represented as an underestimate: UEFA ruled that the “Other Income” line included above for 2011-12 and 2012-13, totalling £60.5 million (€76.9m, $94.7m), was inadmissible since it comprised sales of airy “intellectual property”, the bulk of which went to fellow subsidiary companies of the Abu Dhabi United Group.

From an FFP point of view, the club’s performance in their 2011-12 Premier League-title-winning season and the subsequent one, when they reached the FA Cup final, were absolute disasters. But that said, the turnaround in a mere 12 months since has been quite extraordinary.

The greatest contributor to their financial recovery was the Premier League. Its broadcast distributions to City, who lifted the trophy on the season’s final day, rose 58.6% to £101.9 million (€129.4, $158.8m). Also rising were the club’s commercial incomes, by a very impressive £22.8 million. UEFA, which has closely monitored City’s commercial arrangements with related-party sponsors, will check whether these funds have been raised at market rates – in its “settlement” with City it required that the club would “not seek to improve the financial terms of two second-tier commercial partnerships”.

What will be more interesting still to UEFA is how the revenue upside was reinforced by a reduction in the wage expense, which fell 12% to £205.0 million ($260.1m, £319.6m). In this latter element, City have been quite creative.

According to the accounts there was a very severe reduction in headcount, from 449 to 314 – a staggering, DRINK-ME shrinkage. This implies a wholesale UEFA-enforced redundancy of the workforce that took the staff down more than 30%. Given that City is an important local employer in the Eastlands area of Manchester it is puzzling that there have been no tremors in the press in relation to a grave UEFA-enforced cull creating substantial job losses.

It seems the journalist Nick Harris had the answer as to why this is on the Daily Mail Online website last week. He reported that City had explained to him the reduction in headcount was due to the 100-plus football staff now being paid via other entities in the Abu Dhabi United Group. The club said they are then billed for the outsourced services. City do not appear to have contested the Mail’s report, which is now over a week old. (Although a spokeswoman for the club has declined to engage on the club accounts with Insideworldfootball, despite several attempts to discuss them in more detail.)

Still, the disappearance of any directors’ emoluments from the accounts for the club’s UK parent company, Manchester City Limited – effecting a multimillion-pound saving – might point to the accuracy of Harris’s claims. In the 2010-11 season, City were paying £2 million (€2.5m, $3.1m) to directors but over the course of last season this had been reduced to only a four-figure sum.

The club’s cash operating costs over and above wages have risen £27.8 million (€35.2m, $43.4m) year on year, which would be consistent with the €20 million UEFA fine alongside the outsourcing and rebilling for £10.8 million (€13.7m, $16.9m) of staff costs as reported by the Mail. The 2012-13 bill may have been elevated due to the dismissal of the manager Roberto Mancini and his staff. But there is no question this off-balance-sheet accounting for those employees has definitely created efficiencies, as the overall salary expense fell by £28.1 million including social-security and pension contributions.

This whole area of outsourcing payments to staff through non-licensed affiliates raises intriguing FFP implications. How can UEFA as licensor be sure that what is rebilled by fellow group companies is consistent with the amount of time these staff spend on City affairs? UEFA has previously rejected the “intellectual property” sale to fellow group companies, but is this process merely repackaging it?

Although City’s is a small-scale incursion into off-balance-sheet diversion, the experience of other industry sectors shows the whole area is a potential bottleful of poison. The Bank for International Settlements found in its 2009 working paper “The US dollar shortage in global banking and the international policy response” that the difficulty in tracing banks’ true liabilities through overseas affiliates had contributed significantly to the global credit crisis. If BIS, the bank for central banks, cannot have a handle on the offshore assets in its industry, UEFA’s chances of understanding the expenditure of clubs that hive it off balance sheet are nil.

As soon as things are pushed offshore it opens a huge potential loophole for clubs with wealthy benefactors. The nature of the club-licensing environment is for clubs to account for all their income and expenditure through a holding company whose reports are available to the UEFA licensing body. These are the football rules. But there is nothing in law to back them up, and it leaves the FFP system open to abuse.

Football already uses the offshore environment routinely, whether for club ownership structures or for commercial and broadcasting entities that generate international revenues for clubs. This brings a number of efficiencies. Top footballers, too, have used offshore entities to structure their pay.

Although paying players through deliberate tax-avoidance mechanisms offshore, such as misused Employee Benefit Trusts, can create big difficulties with inland-revenue services, there is nothing illegal in paying someone offshore as long as the requisite tax is paid on the income.

Normally clubs who have used such mechanisms have been trying to divert more cash into player wages by reducing concomitant tax liabilities, thus enhancing team performance. If players demand to be paid millions of pounds in wages net, then the less tax paid means a better calibre of player can be acquired. But this can be a dangerous game of taxman jeopardy, as Arsenal found to their multimillion-pound cost in the last decade.

That said, if prior to FFP a club had not been operating entirely from within its own resources due to the supreme wealth of its benefactor, these considerations do not apply, because the imperative has always been for football success at any cost. A multibillionaire owner or sovereign-wealth fund can foot players’ top-layered tax payments and shrug them off as pocket change.

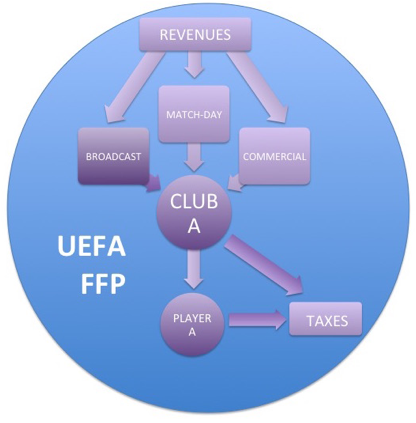

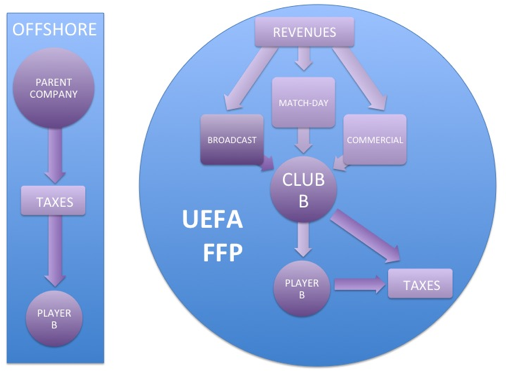

Compare the two slides below, where the first, Club A – operating entirely on its own-generated resources – puts all of its player-salary payments through the FFP-scrutinised books, and the other, club B, offshores some of its player-wage payments.

Now although I have introduced this concept in a column about Manchester City’s FFP compliance, it must be underlined that there is absolutely nothing to suggest that City have used the offshore mechanism above. This goes way beyond paying a few directors or even dozens of football-analytics staff through off-balance-sheet entities.

The purpose of the above images is merely to illustrate how the clubs with the richest benefactors might be tempted to use perfectly legal offshore mechanisms (provided the requisite taxes are paid) to avoid the scrutiny of UEFA’s licensing body altogether. If money-no-object Club B wanted to hire Cristiano Ronaldo, Lionel Messi and Manuel Neuer all at once, it could pay them a manageable salary of, say, £10 million (€12.7m, $15.7m) a year each through the books of the FFP-scrutinised entity and then top it up with any amount through the offshore mechanism.

There really would be nothing UEFA could do about it because they could never know if this sort of thing is going on. The licensor relies on the timely and honest provision of clubs’ annual reports and accounts. Clubs or their parents making payments through structures using the tax-haven secrecy of offshore entities could never be found out, because UEFA cannot look into cash movements through tax havens in the way that some tax authorities can.

So UEFA has a big decision ahead. It might be satisfied with City’s new employment arrangements and allow workers to be sub-contracted out from the club’s affiliate companies. But it should be aware that tolerating any off-balance-sheet activity at all is to go down a rabbit hole from which there is no return.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745269879labto1745269879ofdlr1745269879owedi1745269879sni@t1745269879tocs.1745269879ttam1745269879.