February 9 – Analysing the Premier League’s case against Manchester City

“Croesus; man is entirely chance, and nobody knows what the gods may bring tomorrow.” Herodotus, The Histories

For Croesus, the great king of Lydia, whose name has reigned through 25 centuries as being a synonym for riches, life was pretty swell. He challenged Solon, the Athenian philosopher, to name a happier man alive. He was certainly surprised when told it was not him.

Still, he soon discovered the truth of Solon’s words when, days later, the king would find himself on a blazing funeral pyre after the invasion of Lydia by the Achaemenid king, Cyrus the Great of Persia. Wealth, it turns out, is no guarantor of a long and happy life.

But it certainly helps. Manchester City have reigned supreme over English football for four of the past five completed seasons. Managed by Pep Guardiola, the linear heir to the great Rinus Michels, and funded by the wealth gushing from Emirati oilwells, life has been pretty swell for all associated with City too.

Since 2010, their big-six rivals have suffered volatile league finishes, with every one of them spending at least three years out of the top four. Not City, who have been the only English club to qualify for the Champions League for the past dozen completed seasons. This sustained consistency, in a period of ferocious competition driven by unprecedented global interest in the English game, has been nothing short of remarkable.

What could possibly go wrong? Well, as Herodotus himself would surely recognise, there are certainly signs of more than a bit of hubris over at Eastlands. On Monday, Manchester City were charged with 115 alleged breaches of Premier League regulations across 14 seasons, from 2009-10 to the current one.

City have been through this before, when UEFA charged it with multiple breaches of its Financial Fair Play regulations. UEFA’s case was successful but the decision to ban City from its competitions for two years was overturned at the Court of Arbitration for Sport on a technicality, due in part to the time limits on the admissibility of evidence. The CAS decision could not dissuade Yves Leterme, a former chief investigator at UEFA, who was quoted this week as saying: “I am convinced that fraud has been committed by Manchester City.”

He alleged: “It turned out that money from sponsorship was actually paid by the owner. There were also ambiguities surrounding contracts. However, thanks to emails and bank statements, we had hard evidence.”

The Premier League is unencumbered by time limitations and is not obliged to submit to the judgement of CAS, since the decision of the independent committee to be convened to hear the case will be binding. But it will face just as much of a fight as did UEFA. According to The Times, City have hired the redoubtable Lord Pannick KC to fight their case. They seem as determined as in their previous legal wrangles. “With a battery of lawyers, they did everything they could to counter the work of our auditors,” added Leterme in an interview with Sporza. “There was a total lack of transparent flow of financial information.”

Financial transparency has long been in short supply at Manchester City. Almost 10 years ago I wrote about the curiouser and curiouser growth in their revenues and shrinkage of their wage bill.. Since then things have become still more impenetrable. Exactly how City go about their football operation is impossible to tell, since they have been obfuscating their activities from public view by conglomerating a global football operation of multiple clubs under the aegis of the City Football Group.

Club-licensing rules dictate that teams must surrender their management accounts, but whether City’s have provided a true picture seems, from Leterme’s words at least, to be moot. Indeed, the very frustrations Leterme’s team encountered are echoed in the Premier League’s charge of non-cooperation with its investigation, across four years and more.

City denies this, as so much else, saying: “Manchester City FC is surprised by the issuing of these alleged breaches of the rules. Particularly given the extensive engagement and vast amount of detailed materials the League has been provided with. We look forward to this matter being put to rest once and for all.”

Other charges relate to irregularities in the payments made to Roberto Mancini during his tenure as manager between 2009 and 2013. According to the Football Leaks documents published in Der Spiegel in 2018, which triggered the Premier League investigation, he was paid £1.45 million net of tax and another £1.75 million to his company for football consultancy at CFG club Al Jazira. The latter was in respect of four days’ coaching per year.

There are also charges over the salaries to players between 2010-11 and 2015-16. Others still surround the sums received in commercial income, allegedly from related parties. As the football-finance commentator Kieran Maguire stated to BBC Radio 5, the matters raised in my 2014 column are very much coming to roost: “The allegations made by the Premier are threefold: that Manchester City has overstated the money coming in through signing deals. The accusation is that some of those deals are inflated because it’s actually money coming in from the owner but is being disguised as commercial income.

“Secondly, there has been deflation in costs through the use of parallel contracts. And if you put those two together – more money coming in, less money going out – that means you end up within the cost-control limits that we have within football.

“The third allegation is that Manchester City have prevaricated and delayed the report. The investigation has taken longer than World War One, a huge amount of time.”

Much is at stake for City, with the possibility of points deductions and even enforced relegation if the charges are proven. When in 1992 Swindon Town’s chairman, Brian Hillier, was found to have funnelled payments to players without paying tax on it, the Wiltshire club, which had won promotion to English football’s top division that season, was instead relegated to its third tier.

Hillier’s defence was that off-the-books payments, amounting to a low, six-figure sum across just over four years, were commonplace in football. The judge responded: “If that were to be the case, though I do not accept that, it is high time someone was made an example of to see it does not happen again,” and promptly jailed Hillier for six months.

Whatever transpires in the City case, it will take months at least to conclude. In the face of City’s alleged obfuscation, which the club denies, what can we tell of the strength of the Premier League’s argument? It is instructive that since 2017-18, through being subsumed in the broader City Football Group financial structure, Manchester City have been unique among big-six Premier League clubs in not making public their cash spending on transfers.

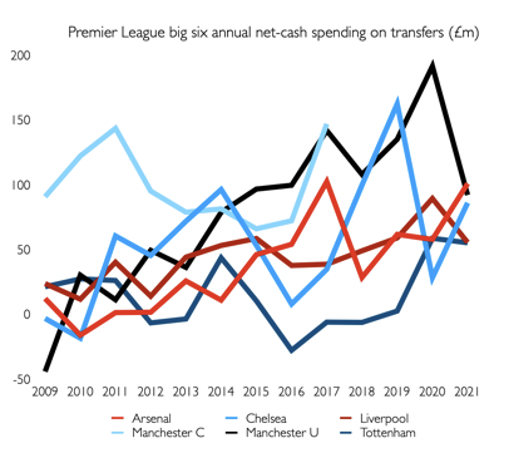

The chart below provides a view of the year-over-year cash spending on transfers for City and its big-six peer group. The figures are net of new signings and player sales and run across all seasons for which data are available since the Abu Dhabi United Group’s September 2008 takeover.

As you can see, City outspent all five other clubs in six of the eight seasons to 2017-18, when the numbers suddenly became unavailable. (Because they tend to be part of wider groups, for all the charts below, I have compiled the data using the annual reports of the most senior UK-registered entity among the group companies that accounts for that club alone.)

By the end of the 2015-16 season, this all added up to double the cumulative net-cash transfer investment of their biggest-spending big-six rival, Manchester United, who took fully three more years to eclipse City’s total from 2017. Precisely what City’s would have run to in cash terms by 2021, they have not made available.

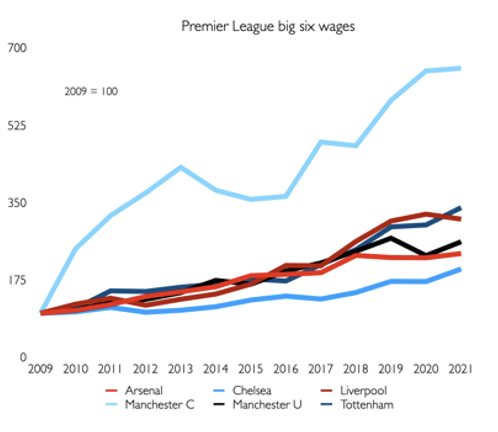

But transfer spending is only ever half the story of player investment. And the remarkable shrinkage in wage expenditure I identified in 2014 turned out not to be a one-off but was repeated in the following two seasons. The chart below demonstrates the relative increase in player-wage bills when taking the end of the 2008-9 Premier League season, Abu Dhabi’s first at City, as the baseline.

Although beginning from a lower base than the rest of their big-six peers, it was not dramatically so, with their 2008-9 wage bill standing at only £6.2m, or 10%, less than Tottenham’s. The advantage of representing the data in this way is that it provides the clearest insight into the year-over-year trends.

The chart above plainly demonstrates how City’s wage bill, amid a general trend in wage inflation for the Premier League’s other big-six clubs, temporarily undergoes a large relative decline, beginning a decade ago. Dips in clubs’ wage bills can often be explained by reduced player-bonus payments, such as for Manchester United in 2015 and 2020. In each of the previous seasons, United had finished outside of the Champions League qualifying places, reducing the associated wage burden.

But that was surely not the case at City, whose wage bill even fell to a four-year low in 2015 when they finished second in the Premier League and had qualified for that season’s Champions League as champions of England. It is also, perhaps, noteworthy in the context of the Premier League charges that another decline in wage costs in the 2017-18 season turned out only to be a blip.

Within six months of the year end those accounts related to, the Premier League had opened its investigation into City’s financial affairs. Within 18 months of that, £100 million had been added to the club’s reported wage bill. Coincidence? It seems the Premier League’s legal team thinks not.

In a world of FFP rules, all wage and transfer obligations must be provided for by income generated from the club’s operations – media, broadcasting and commercial revenues – with a limited, allowable subsidy from owners. For a club like Manchester City, whose gate revenues are typically half those of their neighbours Manchester United, this is difficult.

Fortunately, such is the enthusiasm in Abu Dhabi for the ownership of City by Sheikh Mansour, the chairman of the Emirates Investment Authority, that several state-owned enterprises from the emirate of Abu Dhabi invest heavily in sponsorships of the club. Etihad Airways, as shirt and stadium sponsor, along with Emirates Palace Abu Dhabi and Experience Abu Dhabi are three of City’s top-tier “global partners” today.

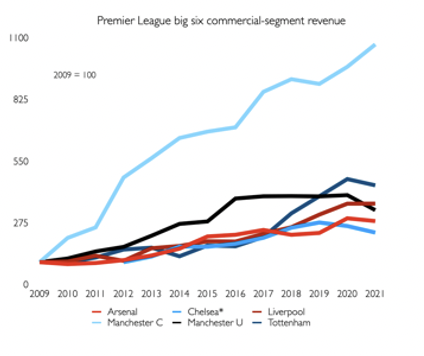

This has contributed to the vaulting growth in City’s commercial revenue. (In the chart below, no data were available for Chelsea between 2008 and 2011, since it did not disaggregate its broadcast and commercial revenues until the 2011-12 season.)

Again, by using the 2009 baseline (2012 for Chelsea) we can see the trends reflected. City’s consistent improvement in their relative commercial revenue stands out starkly against other big-six clubs’. For all of them bar Liverpool, Covid had a dramatic impact, causing a material dip in revenues relative to their improving trendlines. Not for City, however, whose own continued marching upwards, seemingly unhindered by the market forces that had caused United’s to stall between 2016 and 2021.

In football terms, City truly have been as rich as Croesus. The club counter, in a defence frequently parroted by their fans, that the largesse of Abu Dhabi has, like Croesus’s gilded palaces in Lydia, done much to regenerate east Manchester. But if proven, this cannot absolve rule-breaking. Sporting competition must be founded in integrity and good-faith conduct. Without that, the game itself is compromised.

Another trope of City’s defenders is that all clubs should be permitted to spend what they want; if they have the resources and it is their money, then why should they not? After all, so they say, investors can do this in any other business.

But this completely overlooks two important facts. First is that the business world is not an unfettered free market – competition law and antitrust regulations try to bring some measure of discipline to any wrongheaded investment that might impinge on consumers. Second is that football-player investment is not a zero-sum equation.

Increased wages for one set of players leads to raised expectations from another set, leading to a less sustainable market altogether. For all the meagre trickle-down economics of player purchases, the general wage inflation those expectations create is highly damaging for the football economy at large.

And if clubs are forced to spend ever more on labour costs, what will they have left over for infrastructure improvements that might lead to their regenerating the local area around their stadium footprint? It is impossible to prove the counterfactual, but it is conceivable that in a more disciplined wage environment, clubs could do more for their local communities than they can currently afford.

Croesus, it turns out, escaped being burned alive on the funeral pyre and survived, perhaps lifted away by the god Apollo, more likely captured by his conqueror Cyrus. It is said that, chastened and stripped of his land and titles, he became a loyal subject of the Persian empire that had overrun him. What will become of the Premier League’s Citizens now?

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745356053labto1745356053ofdlr1745356053owedi1745356053sni@t1745356053tocs.1745356053ttam1745356053