Fabio Capello’s dig at Wayne Rooney that the England star striker only understands “Scottish” has raised a few hackles. It was in response to comments by Rooney that under Roy Hodgson there are no language problems in the English team.

This has generated much debate about whether a team can perform well unless players and managers share a common language. The Italian (pictured below, second from right), who has been criticised for not learning English, was clearly getting his own back – and, I suspect, also having a joke at Rooney’s expense.

However, to reduce the problem of player management to purely that of language is to simplify and distort a very complex process. Man management of a team, and how players perform for a particular manager, goes much beyond whether or not the manager speaks the same language as his team.

Not that language does not matter. And in the case of Wayne Rooney it must be said that his own use of the English language has often baffled many. I have a very vivid recollection of the problems this caused back in the 2004 European Championship. That was the championship when Rooney stamped himself on the European stage, suggesting he could be the talismanic player who would finally end England’s hurt and win its first trophy since 1966.

England had gone into Euro 2004 with a golden generation, but started with a defeat to France despite having led and even at times outplayed the holders. However, Rooney then duly appeared and scored two stunning goals which beat Switzerland and offered hopes of glory, only to end, as it so often does for England, with the all-too-familiar penalty shoot-out defeat.

However, it was after Rooney had mastered Switzerland in the brief English spring of that summer that language propped up. Rooney was, unsurprisingly, the chosen man of the match and this meant he had to come to the post-match press conference and answer some media questions.

The occasion was important because such access to players is rare. Generally you get a fleeting chance to talk to players in the so-called ‘mixed zone’ when journalists line a corridor along which players travel as they go from the dressing room to the team bus.

If you have not witnessed it, it is hard to believe that we in the media put up with it – but we do. There we stand, like hawkers in a bazaar offering not goods for sale but our microphones, and as the players go by we shout out questions. The hope is that at least some of the players hurrying by will provide the odd sound-bite that will make a story, if not the next day’s headlines.

Euro 2012 has already demonstrated how this system can come unstuck. It was during one such mixed zone encounter that Samir Nasri of France is supposed to have abused a journalist. He has since apologised but it has illustrated the lack of transparency and openness that sport in Europe still tolerates. I say Europe because Americans provide much greater media access to their athletes and coaches, and in a much more civilised fashion.

However, in this case, to accept his man of the match award Rooney (pictured above) had to attend a formal press conference. He sat on a podium in front of a bank of microphones and was inevitably asked how he had scored his goals. His answer was simple, “Michael put it on me head”, meaning his goals were due to the excellent crosses Michael Owen had supplied.

Nothing extraordinary in that. It is the sort of banal explanation most players give at the end of a match. What struck me more was Rooney’s voice. Although he was 19, the tone was more like that of a child whose voice had not yet broken. And he gave the impression that all this media attention was intensely uncomfortable.

It was at the end of the press conference that I realised that Rooney’s words had caused some problems. One of the UEFA press officers approached me and asked if I could help out a couple of journalists, one from Switzerland and another from Sweden. They had both been at the press conference, both knew English well, but they could not quite understand what Rooney meant. When I spoke to them they were very puzzled by a phrase Rooney had used. What, they asked me, did Rooney mean when he said “me head”. They had looked through the English team sheet and could not find anyone of that name. I explained Rooney meant to say “my head”. The Swiss and Swedish journalists were surprised to learn such a use of a very familiar English word. They had spent much time learning English and it illustrated to me how people who may share the same language can often use words in a way that is baffling.

It is worth stressing that at the time England was managed by another foreigner, the Swede Sven-Göran Eriksson. But while his English was much superior to that of Capello, I suspect he may have also had some problems understanding “me head”. But whether he did or not, his failure, and that of Capello’s, to get the best out of England went beyond language. It had to do with understanding the wider culture of the game, the limitations of the country they were managing and what English players can provide at the top level.

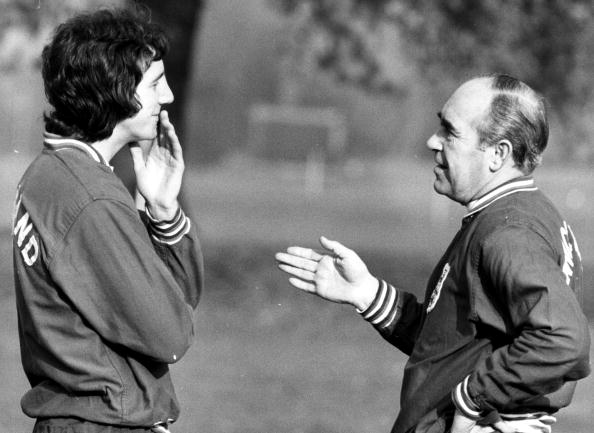

Hodgson who, of course, came to prominence managing foreign teams, understands that all too well. And this, rather than the fact that he speaks the same language as the players, sets him apart from Capello and even Eriksson. Indeed, in this he has more than a touch of Sir Alf Ramsey (pictured above, on right).

Now, England’s only successful manager did not have a great command of his native tongue. He may have never used the phrase “me head” but his use of English could often be as confusing as that of Rooney. What is more he confused not only the foreign press but his own English media…

But what mattered was that he understood how he could maximise the resources at his disposal. This was the reason he led England to World Cup glory. Hodgson has done enough at these Euros to demonstrate that he also understands that. And if he can carry on in this vein then there is real hope for English football – irrespective of the language spoken between players and manager.

Mihir Bose is one of the world’s most astute observers on politics in sport, particularly football. He wrote formerly for The Sunday Times and the Daily Telegraph and was the BBC’s head sports editor.

Follow Mihir on Twitter.