The announcement of Britain’s Olympic football squad has made front page news, not least because of who was left out. Back in 1956, the side for the Melbourne Games was named in instalments and they had already been knocked out of the tournament once.

For the first time, a home and away system of qualification had been introduced.

In those days British international teams were chosen by a panel of selectors. Only then did the manager take over and on the road to Olympic qualification, Great Britain had a new man in charge: Frederick Norman Smith Creek. He had won a full cap for England back in the 1920s as a member of the Corinthians. He was known by his initials F.N.S. and was certainly an “old school amateur”.

“You couldn’t compare him to a manager today,” said Derek Lewin of Bishop Auckland, an Olympic player in 1956.

“If you did not retreat 10 yards at a free-kick, you were not selected for the next match.”

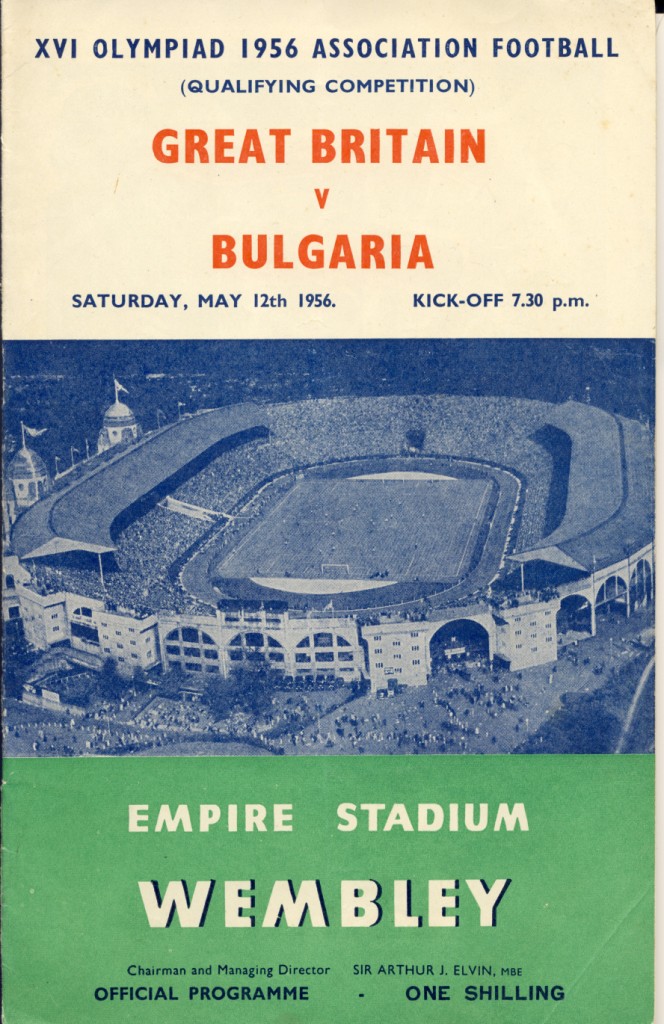

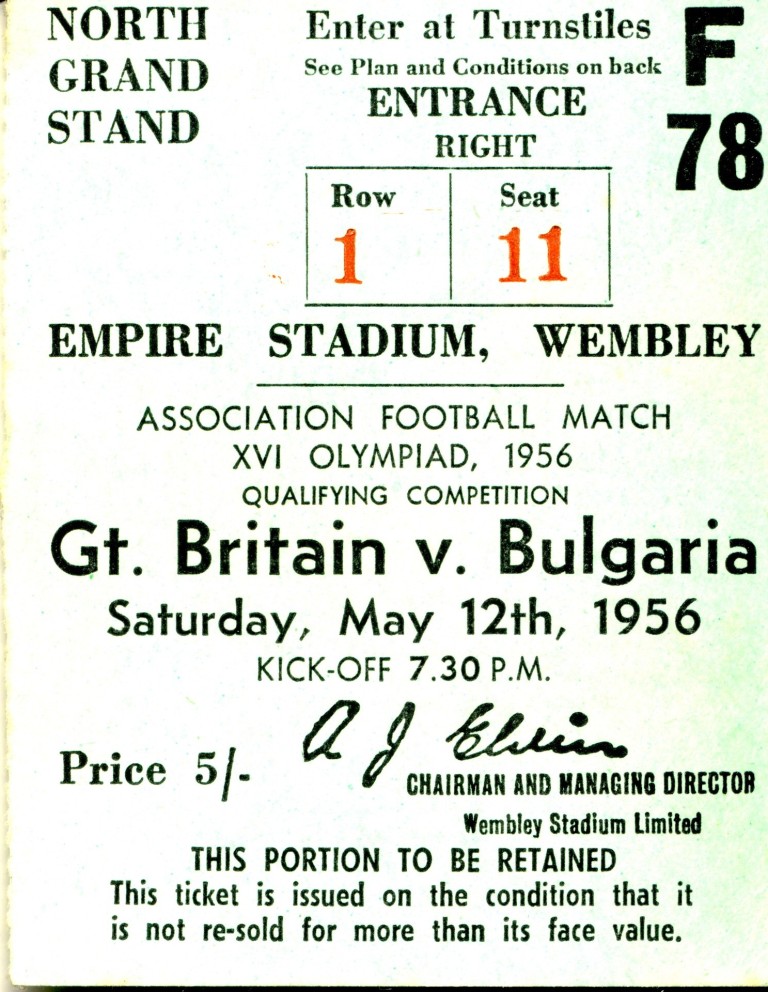

A series of practice matches was arranged against league opposition with varying degrees of success. Then came the first leg of their qualifying tie against Bulgaria in October 1955 (pictured below).

Legendary writer Geoffrey Green travelled with the team. He told his readers in The Times that he had bought a harmonica and hoped for “some street corners in Sofia”. On arrival crowds lined the streets from the airport.

“No British team travelling abroad has ever received a greater welcome than our lads in Sofia. The Bulgarians greeted the team as the kings of soccer, but could not understand the absence of one king – our own Stanley Matthews,” wrote Leslie Nicholls, a contributor the Wembley match programme in the 1950s.

Half-a-million applied for the 50,000 tickets available and nearly a quarter of a million swarmed onto the streets on the day of the match as roads were cordoned off.

“The dressing rooms were the oddest I have seen,” said Olympic veteran Bob Hardisty, another Bishop Auckland player. “The floors were carpeted hanging in the lockers were bathrobes and clogs. There were flowers, bowls of fruit and boxes of cigarettes around the room.”

Once the match started, a corner count of 15 to two demonstrated Bulgaria’s superiority but they only scored twice. Thanks to an heroic performance from British keeper Mike Pinner, who later played for Queens Park Rangers and Manchester United as an amateur

The second leg was at Wembley the following May. British Olympic Association chairman Lord Burghley was presented to the teams as the band played Entry of the Bulgars.

Although Britain scored through Hardisty, the Bulgarians hit back to lead twice but each time Britain levelled the score on the night. Although a 3-3 draw was creditable, Bulgaria had won 5-3 on aggregate and Britain were out of the Olympics.

Very soon they were back in, at the invitation of the organisers. The sheer cost of travelling to Australia made it too expensive for some, others withdrew because of the political situation. This was the year of the Suez crisis and the Hungarian uprising. As Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest many of Hungary’s 1952 Gold medal winning team fled the country.

Not all were happy at Britain’s re-instatement.

“Most officials felt that by allowing the team to play after being eliminated we were flouting the conventions of the competition,” wrote Bernard Joy, himself an Olympian in 1936. “It could not have happened in the FA Cup and the Olympics should surely have had the same strict adherence to the rules. Having been beaten, they should have remained out.”

Scotland Wales and Northern Ireland decided they would not supply players “partly because of the cost and partly because the Olympics will fall in the middle of their home football season.”

England decided to go it alone and clubs were asked for donations towards the cost of the trip. The Essex County FA chipped in with a 100 guineas.

To prepare, the team played further practice matches. The gate money helped with the cost of the trip. Money was so tight they named the squad in instalments. Corinthian Casual David Miller, later a distinguished Olympic journalist, was one who missed out. Future England cricketer Micky Stewart was another unlucky one.

When the squad of 16 flew out, their journey was delayed by eight hours in Istanbul, when the nose wheel broke.

When they reached their destination, they discovered further withdrawals had reduced competition to 11 teams.

Aussie Rules had been included as an exhibition sport in Melbourne.

“Our kind of football was played down in the press, the radio and even in the official handouts, while the solitary exhibition of Australian Rules football was played up,” complained journalist Willy Meisl.

Even so, European teams revelled in the sunshine. The Soviets blasted 15 against a local club side in practice and Britain themselves beat an Australian side 3-1 behind closed doors. They even found time to play a local school at cricket.

Before the first match Britain lost first choice keeper Mike Pinner to a hand injury but this had little effect in the first match against tournament outsiders Thailand. Charlie Twissell of the Royal Navy opened the scoring delighting sailors who had taken advantage of a spot of shore leave to come and watch. A hat-trick from Jack Layborne eased Britain to a 9-0 win.

“Our players towered over their blue clad opponents,” wrote Bernard Joy. “Eleven Snow Whites against 11 Dwarfs.”

Now they awaited the second round draw. It paired them with… with Bulgaria – again! “Poetic justice” said Sir Stanley Rous, secretary of the FA at the time.

The Bulgarians had received a first round bye so warmed up for the tournament with a 16-0 win against a local club side. Thus sharpened, the Bulgarians were quickly into their stride with a goal in six minutes. They were 3-1 up by half time and added three without further reply in the second half.

“To a man the Bulgarians trapped, kicked and headed better, and indeed attempted feats that our players only try in practice,” said a report at the time.

Bulgaria eventually lost to the USSR in the semis. The Soviets, helped by legendary keeper Lev Yashin (pictured above), took gold. He was just one of the players who reappeared at the World Cup two years later.

The British muttered darkly of “nations who are prepared to evade the definition of amateur in order to parade their best performers”.

In World Sports magazine Meisl asked: “What sense can it make when, under the sacred Olympic flag, a few almost amateur teams have to compete against Shamateurs of various hues and several super professional sides, usual known as Shamateurs (State Amateurs)? No sense at all of course.”

The problem was to dog football until at last the professionals were finally admitted to Olympic tournaments in the eighties.

Philip Barker, one of the world’s most renowned sports historians, is the author of The History of the Olympic Torch, published by Amberley recently. To order a copy click here.

Philip Barker, one of the world’s most renowned sports historians, is the author of The History of the Olympic Torch, published by Amberley recently. To order a copy click here.