“In one way the constant battling was very good because what it did was make them very competitive. Horst and his family were all very aggressive and all very successful.” Former Horst Dassler aide Patrick Nally, as quoted by Andrew Jennings and Vyv Simson, The Lords of the Rings.

As the president of Adidas, Horst Dassler was until his death in 1987 arguably the most powerful man in sport. One-third of “The Club”, a secret troika involving the then International Olympic Committee chairman, Juan Antonio Samaranch, and the then FIFA president, João Havelange, he was described by his close associate, Nally, as “the puppet-master of the sporting world”.

Power never evolves without conflict and indeed Adidas’s German sportswear rival Puma was born of an almighty argument – between Horst’s father, the Adidas founder, Adolf, and his brother (Horst’s uncle), Rudolf. Aggression has been in Adidas’s DNA since the very earliest phase of its development.

Decades later, it remains a plain-speaking outfit, as Liverpool found last year. The chief executive Herbert Hainer disparaged the five-times European champions’ diminished on-field performance as being “not in balance” with what it had asked for in failed sponsorship negotiations with its former kit manufacturer.

Liverpool is at least far from alone in being publicly disdained by Adidas, and last week Sports Direct’s chief executive, Dave Forsey, splutteringly revealed how his firm had fallen foul. Adidas will refuse to supply it with Chelsea’s replica kit for next season, the 2014-15 campaign. “We just can’t understand how it can possibly be right,” said Forsey.

But the auguries of tensions between the supplier and the retailer had already been there for the reading. A leading UK retail analyst told me on condition of anonymity a story that came from a recent Sports Direct shareholders’ meeting. Mike Ashley, its controlling shareholder, held two Adidas football boots aloft: one black and one blue. He explained to his audience how over the coming season 90% of footballers will wear blue, green or yellow boots while the referees and only a small number of contrary players would be wearing black.

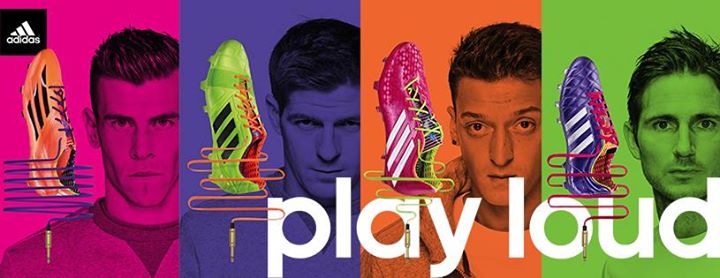

To Ashley’s chagrin, even prior to the Chelsea spat Sports Direct was permitted access only to the version in black. Sports Direct’s biggest rival, JD Sports, currently has no such problems, as this prior cover photo from its Facebook page, also used widely in a poster campaign, proves.

JD Sports/Adidas poster campaign

(Source: https://www.facebook.com/JDSportsOfficial)

But despite the strained relations between them it is worth noting how good Adidas and Sports Direct have been for one another. As Adidas’s 2013 group accounts note: “In 2012, revenues in Western Europe increased 3% on a currency-neutral basis, primarily as a result of double-digit sales increases in the UK and Poland.”

This is reinforced by the commentary in the Adidas UK report for 2013: “Sales increased by 10.8% (2011 3.81%) versus the prior year to £541 million (2011 £488 million).”

It all adds up to the UK revenue share being a far-from-insignificant proportion of Adidas’s European income base, contributing €666.3 million over the course of the year. Given that the entire Western European sales base for Adidas amounted to €4.076 billion, it means that almost one in six of all euros it received across the region came from the UK.

And that means a lot of the heavy lifting was done by Sports Direct, in whose grip the UK sports-retailing market is held. Built from nothing by Ashley, its no-frills outlets on Britain’s declining high streets and soulless out-of-town retail parks combine to make a £4 billion business that is listed among the UK’s leading 100 companies on the FTSE100.

Sports Direct is six times bigger in terms of market capitalisation than JD Sports and it accounts for 57.6% more in terms of revenues, meaning Sports Direct is clearing a far bigger volume of units.

Yet it is the way that income is derived that Adidas finds objectionable. There was an echo of the combative Dassler family in its commentary as to why its fraternity with Sports Direct had broken down and it would pull out of distributing products through its stores. There was certainly more of the Robert Huth hoof than the delicate Mesut Özil touch in the German kit manufacturer’s explanation.

“Like all manufacturers, we regularly review, season by season, where our products are distributed,” Adidas said. “We determine distribution channels for all products based on criteria such as in-store environment and customer service levels.”

Ouch. It is fair to say that Sports Direct’s flagship store on London’s Piccadilly Circus, Lilywhites, is no longer the upmarket cathedral to sportswear that it was prior to Sports Direct’s takeover. And the German company’s statement was a (slightly) more-corporate lament than the one I have frequently heard about SD from people in English football. Basically lots of people feel Ashley and Sports Direct’s modus operandi debases the brands it sells by housing them in discount buckets more akin to rummage sales than to premium retailers.

Yet I am afraid that for me, there is something about Adidas’s attack on Sports Direct that just does not wash. As the UK-retail analyst told me: “Adidas need Sports Direct. They’d see a big drop in UK turnover without it. It’s a good clearance yard for them.”

A fearsomely hard-working self-made billionaire, Ashley has not brought the warehouse-style approach to his firm’s retail operations through laziness. He has developed it because that’s what appeals to his customers.

And Sports Direct’s pile ’em high, sell ’em cheap philosophy has been paying dividends to Adidas. Once their top offerings have failed to sell at the higher-end retailers, they can be shipped off to the knackers’ yard on the dilapidated high street to be sold off at a tremendous discount. Yet now Adidas has eschewed this better-to-sell-for-less-than-not-at-all philosophy, like some nightclub bouncer denying access to a man in the queue because he is wearing Adidas trainers. Why?

One reason is certainly that the German retailer is seeking a more premium status in the sportswear market. It has launched proprietary Adidas Originals stores in more than 30 global cities, aimed at taking back control of how its products are marketed and sold.

It seems that, like Burberry before it under Angela Ahrendts – who rejected the football-hooligan culture that had ripped off the luxury brand’s designs – Adidas does not want to be associated with the ‘undeserving poor’ and will seek to price them out of its football-product ranges. But there might just be another explanation for Adidas’s aggression towards Sports Direct.

The argument between the two multibillion-pound sportswear firms centres around Chelsea kits, after all. And the decision not to permit Sports Direct stocking rights to those kits in the 2014-15 season comes about six months after Adidas and Chelsea signed a £300 million, 10-year deal over the supply of the club’s kit. Chelsea, who certainly will be allowed to stock the kits, have been conspicuously silent on the row. But there is no doubting that Adidas’s decision certainly serves the club’s long-term interests.

Ashley owns not only Sports Direct but also Chelsea’s Premier League rivals Newcastle United. By no means would I suggest that Chelsea has connived with Adidas to prevent Sports Direct earning revenues for the Newcastle owner, because they would be negligible to his and Newcastle’s operations in the grand scheme of things. (It would also be too much of a stretch to insinuate that Newcastle dropping Adidas in favour of the Puma logo it hates so much in the 2010-11 season had anything to do with it.)

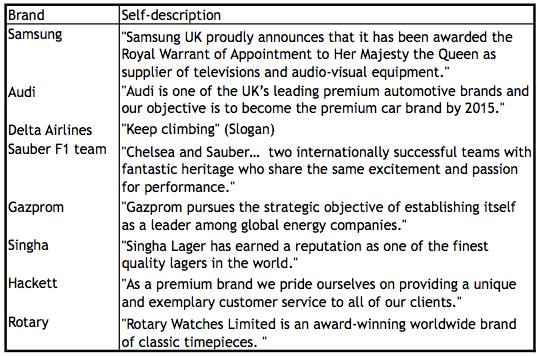

But where there is some payback for Chelsea is in the brand values and, under the chief executive, Ron Gourlay, the club has distinctly been moving upmarket. Chelsea is one of London’s most-exclusive areas and, since its former owner Ken Bates was chairman, has long been charging a premium price for its matchday product. A glance at Chelsea’s list of sponsors reinforces this impression of reinvention from a club that once wanted to cage its unruly supporters behind electric fences into an opera house of football.

Official Chelsea club sponsors

From the Queen’s TV kitemark for Samsung to the awards won by Rotary for its “classic timepieces” Chelsea is aligning itself with brands who push themselves as premium marques. Sports Direct and the demographic it serves suit this company as well as the cigarette-smoking father of eight with his gut hanging out of his Chelsea shirt of stereotype would fit in at the Débutantes’ Ball for Harrogate Ladies’ College.

This gives us clues as to the direction of travel for Chelsea and for their other top Premier League counterparts as football businesses, and it does not bode well for ticket prices at Stamford Bridge and beyond. But given its history of aligning itself with football’s most powerful entities, you sense Adidas, the firm once led by Horst Dassler, the man at the top of “The Club” and sport’s great “puppetmaster”, will do everything it can to help.