“Key ECB interest rates will remain at present or lower levels for an extended period of time,” Mario Draghi, ECB president, reaffirming the 0.5% European bank rate on 1 August 2013.

Ever since the financial crisis first struck, central banks across Europe and beyond have been locked in an arm wrestle with the invisible hand of Adam Smith’s markets. There has been much talk of a zero interest rate policy, of “increased liquidity” and of government-sponsored schemes such as Funding For Lending in the UK. But the fact is small- to medium-sized businesses, a sector including most European football clubs, are finding it harder than ever before to access the capital they need to invest in their businesses.

For some clubs this has not been too much of a problem. As revenues have increased over the course of the past five years the lucky ones, like Arsenal for instance, have even been able to reduce their indebtedness [see: http://www.insideworldfootball.com/matt-scott/13109-matt-scott-why-arsenal-s-cash-mountain-may-remain-just-that]. Rampant global interest in English and Champions League football has been of supreme benefit to the haves, whose media incomes have rocketed. But what of the have-nots who are trying to keep up?

A clue lies in a report sponsored by the European Clubs Association, which was released with little fanfare this month. The study, entitled Project TPO, was conducted by the accountant KPMG, and it points to increasing creativity in the way clubs seek the funding that will plug the gaps in their incomes and maintain their competitiveness.

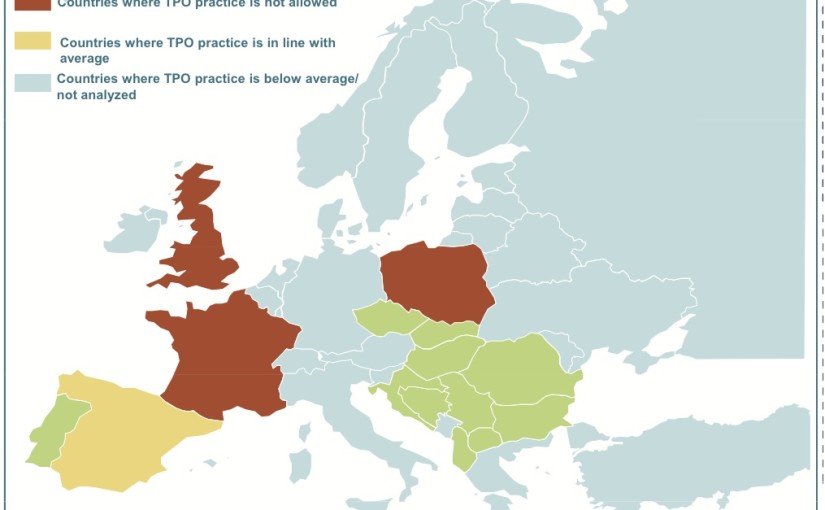

TPO stands for Third-Party Ownership, by which clubs sell a portion of the future value of a player’s transfer fees, most often to a fund of anonymous, offshore investors, in return for cash up front. The KPMG report published an interesting heatmap that shows where the activity is most prevalent.

Third-Party Ownership Heatmap

Source: KPMG, Project TPO

Across Europe it is estimated that between one in 27 and one in almost 17.5 players belongs at least in some part to a third-party owner. Once the territories where the practice is banned are excluded, that proportion rises to between one in 20 and one in almost 12 players.

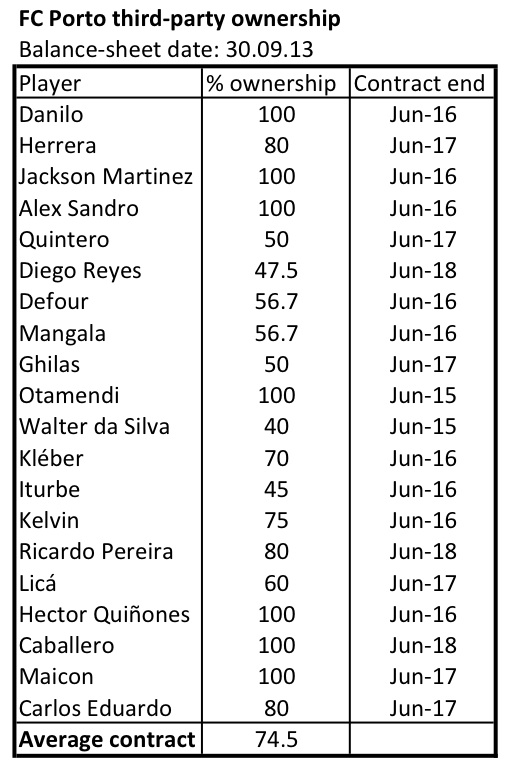

In some territories, though, there is a higher instance of the practice than elsewhere. KPMG found: “TPO is a common practice in Portugal, and the value of the players under TPO practice is between approximately 27% and 36% of the market value of the players in the Portuguese league.”

A glance at the accounts for the two-times European champions FC Porto proves this.

FC Porto third-party ownership

Source: FC Porto consolidated accounts; Q1, 2013-14

Although by no means widespread, as KPMG notes, the employment of TPO mechanisms seems to indicate relative distress in the leagues and clubs who resort to it. It is notable, for instance, that Portugal’s guaranteed share of UEFA Champions League income from the ‘market pool’, generated by the size of a nation’s domestic TV market, was a mere €7.028 million last season. This compared to €58.9 million in France, €72.6 million in England and €81.1 million in Italy.

With such limited broadcast incomes available, cash flows for investment in players are reduced and few lenders would extend credit to help them keep up with the French, English and Italians. As KPMG explained: “The use of TPO in recent years appears to be increasing, as the access to other financing tools appears to be more restrictive. In many cases, TPO is the only financing mechanism which clubs can use, normally implying higher interest rates.”

This is one of the biggest problems with zero interest rate policies: debt is cheap and freely available if you can afford it, but those who might not be able to afford it present a bigger credit risk and therefore must pay more to borrow. The economist Smith would no doubt identify an unintended consequence of the policy: that it exacerbates still further the wealth divergence between rich and poor. Indeed, what is most interesting about the map above is that, save for Greece and Ireland, whose football economies are not of the same size as other European countries, it roughly corresponds with the nations hardest hit by the financial crisis. The difference between the German Bund and individual creditor nations’ sovereign bonds, a general marker for the perceived financial health of a country, have told a tale reflected in the above map. Hungary’s spiked at more than 9% higher than Germany’s in 2009 (and almost returned there in 2011), Portugal’s rose more than 10% and the Czech Republic’s, Austria’s and other nations clustered in central Europe were also substantially above Germany’s.

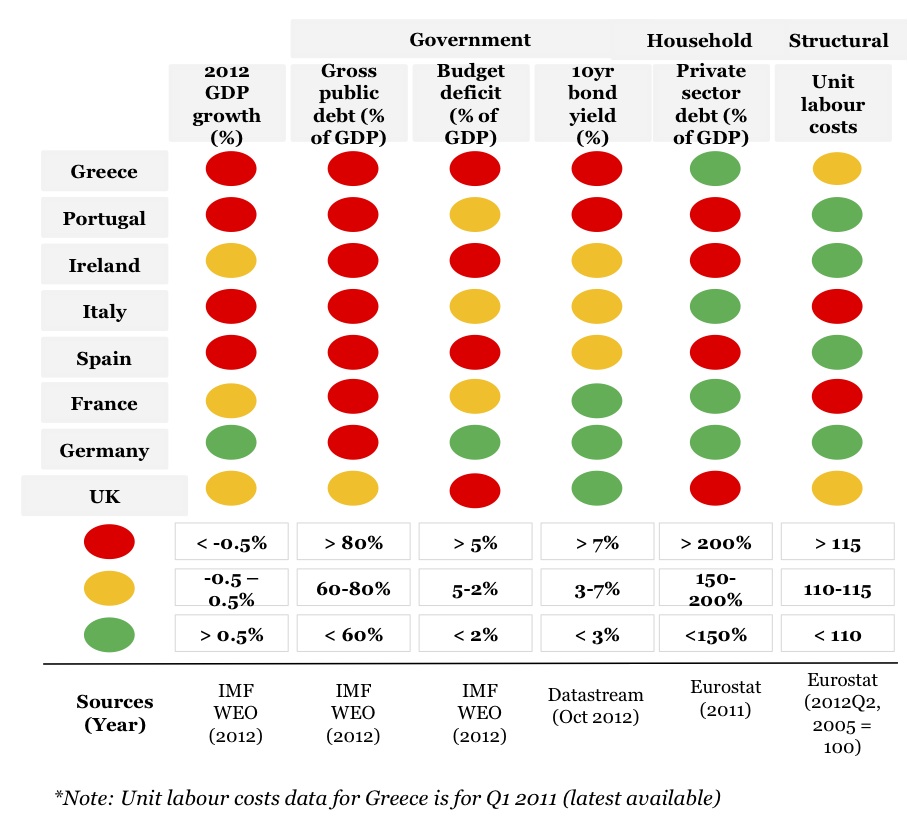

As for the core Eurozone nations reflected above, a report into the debt in Europe by PwC 12 months ago employed a traffic-light system to demonstrate which nations face the biggest risks.

European sovereign-debt risks

Source: Paying Europe’s Debts, PwC.

Of the nations with three or more traffic lights flashing red, only Italy of the big football nations does not frequently employ third-party ownership as an alternative to traditional bank lending. It is perhaps notable that, according to the Palermo, Sicily-based anti-Mafia organisation for business, Sos Impresa, a lot of spare bank capacity is taken up by organised crime. “With €65 billion in liquidity, the Mafia is Italy’s number one bank,” it claimed in a report last year.

Given the lack of disclosure as to the specifics of lending arrangements at Italian clubs, it is difficult to interrogate whether the Mafia has penetrated Italian football in this way. That said, the senior anti-Mafia investigator Pietro Grasso, who is now president of Italy’s Senate, has had his suspicions. “In this time of crisis money that comes at no cost from the Mafia, without bank interest, is welcome for some,” Grasso told La Repubblica in 2011. “If infiltration has occurred in football clubs it would certainly not be for the purpose of financial gain, because the clubs almost never make a profit.

“The reasons may be related to money laundering, although again there are cheaper ways to do it. But it is mainly the pursuit of local consensus that drives them towards the football, because it provides power, which is used during elections for votes.”

So Italian football has perhaps sought its own alternative funding to the constricted bank-lending markets. Even so, according to KPMG, Third-Party Ownership is on the rise.

“Apparently this practice is not common although [it] is becoming more relevant as from the information obtained, investment funds are actually knocking on Italian football clubs’ doors,” the KPMG report found.

So what are the implications of Third-Party Ownership for clubs? Well one thing is for sure: TPO lenders have not extended the near-zero interest-rate policies of the central banks.

According to KPMG’s note on the Spanish TPO market: “The interest rates agreed by the investors in TPO operations are above market conditions… [and] are around 8%-10%. The high returns are justified by the lack of guarantees (the investors are not provided with guarantees such as season tickets or broadcasting rights as these have usually already been pledged to secure other sources of financing).”

Inevitably, the TPO fund does everything it can to reduce these risks in practice.

“For investors TPO agreements represent an opportunity to obtain substantial financial profits and benefits with a relatively insignificant level of risk,” adds KPMG. “All the more since TPO agreements commonly contain clauses stipulating a minimum return on the investment, or clauses providing for the payment of interest, even when the player whose economic rights have been purchased is not transferred within the term of their employment contract. Nonetheless, the risk for investors remains in the potential insolvency of the clubs.”

The risks of such a collapse is something the investment funds reduce by seldom exposing themselves to more than 50% of an individual player’s transfer value. Contracts also provide for one of the most basic elements of a player’s employment status in football: the amortisation of his contract. Naturally a player may sign a club contract for up to five years. If he does not extend that contract and is not transferred out of the club within that time he may subsequently leave for free under a so-called “Bosman” transfer.

However TPO investors insulate themselves against this with “substitution clauses”. These provide for TPO funds whose players do not transfer out of the club before contracts run into their final 18 months (when transfer fees become commensurately discounted) to switch their interest into other of the same club’s players. The club is then left with a player with little residual value who can move on for nothing in pretty short order.

Naturally, although providing a temporary boost to cash-flows as valuable assets are part-sold, such arrangements will increase the volatility of clubs’ transfer activities, perhaps to the detriment of those clubs’ short-term football performance. In the long term, the degradation of balance-sheet assets is also a negative influence. But in an increasingly harmonised football structure across Europe, where the biggest fish in the smallest seas must swim with the ocean giants of Real Madrid, Barcelona and Bayern Munich, what alternative do those on the periphery have?

The answer is, of course, none. But help might be at hand. Perhaps as it earns more from its elite club competition UEFA can be more creative with its distributions to ensure no nation has a 10:1 magnifier over another’s market-pool revenue. Dispassionately it might also be hoped that, as UEFA seeks to save clubs from their own rapacious instincts through FFP, the practice will organically be phased down, if not out. Debts taken on for investment in fixed assets such as the Juventus Stadium, or Tottenham Hotspur’s proposed Northumberland Park development are not to be discouraged as they boost long-term income generation. But generally taking out debt to cover cash-flow deficiencies is a fast track to bankruptcy.

So TPO is akin to households engaging in “equity release” by remortgaging for a short-term cash boost. Or to nations selling off their gold reserves to fund unaffordable obligations in favour of difficult political reforms. And if the people Mario Draghi represents are doing the same sort of thing to the detriment of their nations’ long-term financial health, then what hope does football have?

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1734798927labto1734798927ofdlr1734798927owedi1734798927sni@t1734798927tocs.1734798927ttam1734798927.