“The song of the future must transcend creed.” E.M. Forster, A Passage to India

In India, some call it Sachinism. The legacy of Sachin Tendulkar, cricket’s greatest batsman ever to emerge from the South Asian sub-continent, is so great that he has achieved the status of a demigod in what is already a pantheistic culture. The doleful impact on popular consciousness there of the day he was run out for 99, one run short of a landmark “century”, against South Africa was so deep that it was incorporated in a scene in the Oscar-winning movie Slumdog Millionaire.

Indians love their cricket and it is this passion that has made the 1.6m-tall Sachin a sporting giant. Last November, after 200 Test matches, the Little Master retired from the game in which he made his name. Now, at 40, a new life begins for him. Surprisingly, though, he looks not to the sport of cricket he was born to but instead to the world’s game: football.

This week Sachin and his former India batting partner Sourav Ganguly were among the stars of Indian sport, cinema (or Bollywood) and commerce to invest in franchises for the inaugural iteration of the Indian Super League. Bids for the eight teams apparently averaged out at 1.5 billion rupees (£14.9m/€18m/US$24.9m), which seems a staggering sum for a start-up that produces no income in a country where football has never before gained meaningful traction. (Goa, an island that was once a Portuguese colony, enjoys the game and West Bengal also has a history of following football but these are pockets in a cricket-obsessed nation.) Even so, none other than Spain’s Primera Liga leaders, Atlético Madrid, were said to be among the investors in Sachin’s Kochi consortium. So what is the investment case?

First of all, self-evidently the presence of Sachin in anything guarantees publicity and the attention of millions of eyeballs. His involvement in this venture transcends his own nation’s borders and media coverage extended worldwide. This buzz can potentially be translated into valuable broadcasting and sponsorship contracts. Football in India is also on the cusp of an upward curve in interest. This is because, after decades of persistent reliance on a rural agrarian economy, India is rapidly urbanising.

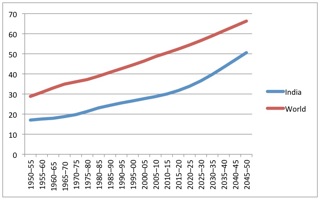

Figure 1. Urban-growth rate in India

Source: United Nations Population Division (2010), World Urbanization Prospects: The 2009 Revision

The experience of the global economy at large shows that with a bigger urban population comes an enlarged middle class, with more disposable income and a greater awareness of overseas affairs. This trend has taken hold in India, where England’s Premier League has captured the imaginations of well-educated middle-class youths who are increasingly urbane and worldly and see an interest in football as setting them apart.

This is the starting point for football’s potential growth in India itself. But there is more to the ISL than a mere punt on the nation’s future economic growth. The tournament is the brainchild of IMG-Reliance, whose past collaborative successes include the Indian Premier League of cricket. Sachin and Ganguly shared in this success, having been ‘icon’ players for IPL franchises from its inception in 2008. From a standing start, the League generated $1billion in domestic television income alone and became a global sporting phenomenon.

The format for the ISL looks the same. Pay an inflated salary to a marquee name from the world of football to act as the figurehead for each team and hold a televised auction for the rest of the talents, mostly Indian. The names of Hernán Crespo, Freddie Ljungberg, Robert Pires, Kenny Dalglish and Peter Schmeichel have been raised in connection with this. It is a marketer’s dream.

However there is something familiar about those names. In 2012 the Celebrity Management Group announced a six-team franchised competition in West Bengal, India’s relative football heartland. Pires and Crespo were among the signed ‘icon’ names. In the absence of a TV deal, the league never got off the ground. There is a strong chance this time it will be different, with Tendulkar, Ganguly et al adding the spice required for it to catch fire in India.

Yet even in spite of its success, the IPL experience shows the ISL faces a number of profound challenges. Allegations of corruption in the IPL strike to the very heart of the Indian cricket establishment. Just this week the former president of Indian cricket’s governing body, N Srinivasan, was named in a judicial report alleging spot-fixing (preordained events in matches for the purposes of cheating at gambling) in the IPL. Twelve cricketers were also named. “We cannot close our eyes after having come to know about the allegations,” said judges from India’s supreme court.

Despite this brouhaha surrounding the very acme of India’s sporting scene, FIFA has remained remarkably quiet on ISL talk. This is no big deal, says Jefferson Slack, the vice-president in charge of IMG’s football division. He claims there are no problems as it has been developed in conjunction with the FIFA-recognised official football governing body there, the All India Football Federation. “FIFA is fully aware of ISL and they are very comfortable with the project,” he told Indian media. “This is not a rebel league and has been approved and allotted a separate window by the AIFF in their calendar.”

INSIDEworldfootball can confirm Slack’s position is also FIFA’s: it told me in an email it is content with the ISL as a competition sanctioned by the AIFF. Provided players’ contractual obligations to their clubs are respected under the Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players, it does not mind who takes part. As in all national leagues, FIFA has devolved governance of the ISL competition to the national governing body, the AIFF. But it is clear that FIFA should monitor closely developments in the Indian sub-continent, where cricket takes place under the shadow of a sophisticated ‘mafia’ operation that is part of a $500 billion global match-fixing industry, according to anticorruption investigators.

Indeed, the former captain, opening bowler and promising young tyro of the touring Pakistan team were jailed in England in 2011 for their part in a spot-fixing scandal that had spilled into a Test match at the home of cricket: Lord’s in London. With football already tussling with the same spectral threats, it would be a desperate shame if the fixers were to use ISL as their launchpad into the game.

That said, with proper oversight, a clean and successful ISL could be a tremendous boost to football worldwide. The game’s relative absence from the popular consciousness in India, the world’s second-most-populous nation, is a shameful anomaly, particularly as a properly engaged Indian diaspora could give football a boost the world over. It is clear the game there needs the impetus of an IPL-style competition to excite the young urbanites who are its future. IMG-Reliance certainly has the track record in sports marketing to grow the format. However, the question of whether the AIFF is sufficiently resourced to guarantee the integrity of its new competition is one that should occupy FIFA too. Proper officiating and tackling corruption are of paramount importance in so high-profile a new competition lest dangerous tendencies take root.

It is clear that with the ISL, the song of India’s sporting future can now transcend its cricketing creed. But football’s orchestrators must make sure it is played in tune.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745314305labto1745314305ofdlr1745314305owedi1745314305sni@t1745314305tocs.1745314305ttam1745314305.