“The strongest of all warriors are these two – Time and Patience.” War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy

Threaded within a fabulously entertaining Napoleonic soap opera, Leo Tolstoy’s masterwork properly explores the human condition. In short, the greatest of all the Russians tells us, if you think you have any free will of your own you are very much mistaken.

Tolstoy conveys that we mortals are swept along by predetermined currents towards outcomes preordained. So West Bromwich Albion fans and shareholders have kind of discovered following the arrival on the scene of their now owner, Jeremy Peace, less than 14 years ago.

That said, the path to his takeover was laid by a matter that was very much under shareholders’ control. It all began in 1994 when the 2,000 stockholders chose to change the club’s constitution. Things had all been very democratic before, with a limit of five votes per shareholder, irrespective of the size of their stake. But this was scrapped in favour of a one-vote-per-share policy in order to permit the club to seek a listing on London’s AIM stockmarket, which took place in early January 1997.

This was in a climate of much excitement about the perceived value of holding a stake in a football club, any football club, and those who determined to trade out of their shares were able to make a lucrative profit. According to Simon Chadwick in his book Managing Football, West Brom floated at £280 a share, valuing the loss-making, mid-table, second-tier English club at a staggering £35 million. Later that month, the professional periodical The Lawyer reported these were trading at £400 each, an instant 43% profit for those who sold their stock. “It shows the intense City interest in football clubs,” was how the Lawyer quoted Stephen Kenny, who advised West Brom’s board on their listing for Wragge & Co. What it really showed was that anyone who truly thought West Bromwich Albion to be worth £50 million (or nearly £80 million in today’s money, accounting for inflation) in early 1997 was barmy. This was a football bubble.

Bubbles burst, as any child knows. Although the general stock market performed well over the next few years, with the FTSE 100 index rising nearly 50% between January 1997 and November 2000, West Brom’s share price tanked along with the value of similarly speculative dot-com stocks. (Between March 2000 and September 2002 the Nasdaq Composite index of telecoms and technology stocks collapsed in value by 78%.)

It meant that when the Baggies sought to replace their 36-year-old Rainbow Stand with a bigger version that was intended to raise The Hawthorns’ capacity from 25,000 to 27,000 at a cost of £5.25 million, they found the project finance hard to come by. The board had no choice but to go back to the market with a rights issue.

This time, though, the shares would be worth a fraction of their previous price. Even accounting for the dilutive effect of the new capital raising, the £70-a-share price was 70% below the initial public offering less than four years previously. The Baggies, with their £6.8 million turnover and continued inability to rise out of English football’s second tier, were now worth a more realistic £10.5 million. Peace, a corporate financier who had previously worked at the investment bank and wealth-management firm Singer & Friedlander, came on to the board in December 2000. Presumably, given Singer’s activities as a lender to football, he had been acquainted with the business of the game. But it was probably more his investment in 1,000 shares through the November rights issue that opened the boardroom door to him.

In a move that Tolstoy would no doubt have relished describing, once inside Peace brought war with him. “Unfortunately I have been forced out of the door rather than being accorded the dignity that I feel my years of hard work and commitment in the service of this club deserves,” said Clive Stapleton in a statement as he departed the acting chairmanship of West Bromwich Albion in June 2002. Soon Peace would have control of the club altogether.

Now they say the only way to make a small fortune from football is to start with a big one. The phrase will mean a lot to Paul Thompson. At the time of the November 2000 rights-issue announcement Thompson had been the West Brom chairman and owned 25.4% of the club. He had taken up some of his rights but not all of them, shrinking his holding in size to 22%. Over time he had paid almost £4.4 million for that stake, through his Highfield Electrical Limited company. By the end of September 2002, though, this was worth less than £2.3 million on a marked-to-market basis. When he came to sell the stake to Peace and others in April 2003, he agreed on £1.7 million, which valued the club in its entirety at only £7.875 million, less than 16% of its 1997 bubble peak.

Though Thompson’s disposal gave him almost 20% of the club, and though he had wangled an incredible bargain, the tireless Peace did not call a truce here. A former employee of the club described his takeover to me as “like a military coup”. Quite: it is probably fair to say Peace weaponised the City Code governing UK-listed companies.

In a statement to the stock market in April 2003 he explained how he had clubbed together with a fellow Baggies shareholder. The Guernsey-based fund Kappa Limited had acquired its holding in tranches, including an £800,000 investment in May 2001 for 11,400 shares. Peace had brought it to the Hawthorns table in the first place, meaning that he was now forming what the City Code describes as a Concert Party. Between them they had owned 29.9% of West Brom prior to the sale of Thompson’s shares, mostly to Peace. But “as a result of the purchase by me today, the combined holdings of the Concert Party in WBA have increased to 70,000 WBA Shares, representing just over 50% of the issued share capital of WBA.

“Accordingly, pursuant to Rule 9 of the City Code, I am required to make an offer for the issued share capital of WBA not already held by the Concert Party.”

Thompson’s sale at £55 per share had set the market price. A substantial number of the Baggies’ shareholders surrendered their stakes. It meant that in less than three months, Peace had raised his holding in the club from 1,000 to 52,370 shares – from 0.67% to 37.69% – and all for less than £3 million. Alongside those at Kappa, 60.37% of West Bromwich Albion’s shares were now under Peace’s control. (A search of the Guernsey Companies Register shows all entities that have ever traded by the name of Kappa have long since been dissolved, while Peace’s own-name-held shares have risen above that 60%.)

What is truly staggering about this achievement is that the Baggies were by now in the Premier League, sharing in a central TV deal worth in excess of £500 million a season. Although the English top flight would suffer a near-20% dip in the value of its next TV-rights cycle following the failure of ITV Digital in March 2002 (perhaps a fact that spooked Thompson into selling out, although the breakdown of his relationship with the then manager, Gary Megson, was certainly the biggest contributor), Peace’s investment would rocket.

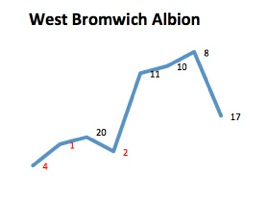

WBA league finishing position, 2006-7 to 2013-14 (red denotes seasons spent in England’s second tier)

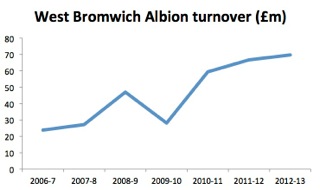

WBA turnover, 2006-7 to 2012-13

In January 2005 Peace delisted West Bromwich Albion and created a new corporate structure under a new umbrella company. More corporate engineering in 2009 saw West Brom’s assets moved out of the 118-year-old former plc company and into a newly formed vehicle. Shareholders were offered £1,200 for each share they held. That might seem a lot compared to past offers, but it valued the club at a mere £12.3 million.

All the while Peace has been patiently accumulating more new shares, and following a tender issued last month, has now closed purchases on shares taking his holding to 76.4% of the club, according to an announcement this week. At least now those battle-hardened souls who have held on throughout it all were able to cash in on better terms than anyone since the first flush of the flotation. This time, Peace paid £3,000 a share.

It was worth every penny to him. the 75% shareholding threshold was a significant figure to cross as he can now unilaterally call the type of extraordinary general meeting, through which his boldest stratagems have frequently been conducted, at will. More significant still, with the club having been paid £65,790,551 merely for being the Premier League’s worst surviving club in the 2013-14 season, no one can stop Peace drawing millions in dividends from what is effectively now his toy.

That could mean Peace taking out cash to cover his entire historical investment over the course of a season or two, while still owning three-quarters of an asset that is comfortably worth £100m. So far the fans have sat quietly by while he has manoeuvred himself into this position. Time and patience have been his greatest allies until now. But if Peace goes precipitately down that road, it might open a war on a new front altogether.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1743697727labto1743697727ofdlr1743697727owedi1743697727sni@t1743697727tocs.1743697727ttam1743697727.