What defines a nation’s football status? Is it the senior-international trophies it has historically won? The depth of its leagues? Its grassroots participation? The quality of its top division, perhaps? Or is it the quality of its national stadium?

As the last century drew to a close, England’s Football Association decided to make the last – and to my mind the least – of those status symbols its principal investment priority. This is despite the fact that, unlike a club’s ground with its dozens of guaranteed fixtures every year, the national stadium lies idle for most of the season. Even so, English football must now feed the gaping maw of debt that went in to building the Wembley National Stadium.

Six years after the venue opened (a year late) the debt the FA still carries over it is £264.1 million. Between January 1, 2012 and July 31, 2013, the FA paid £37.7 million in interest on its loans. Added to that number is the debt service. In 2012, it amounted to £4.6 million. In the 12 months to July this year it was £10.1 million, falling back to £6.1 million in the current 12-month period.

But for the next three years the FA must meet eye-wateringly large payments to their banking lenders. Between July 2015 and July 2018 the FA must pay £76.7 million in repayments alone. Throw in the likely £70 million in debt interest over the same period and the FA must find perhaps £50 million a year to meet their obligations to creditors (although it is mostly loaded into a lump sum in 2017, more on which later).

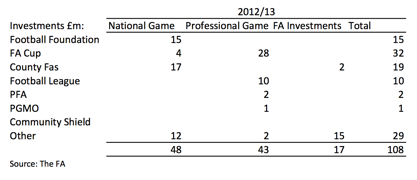

The FA’s highly capable general secretary, Alex Horne, who was formerly its finance director, announced last week he is leaving the organisation to “change direction” and it is possible that this future financial landslide was gnawing at his thoughts. To illustrate the scale of the near-£150 million number impending in the medium term, it is worth remembering the FA’s contribution to the grassroots game in England in 2013 was £48 million.

When things were going well, the sort of interest and debt-service expense that is coming around the corner might have been manageable. But the FA’s fortunes have taken a sharp downturn. The collapse of the satellite broadcaster Setanta, which was a licensee for FA Cup and England matches, cost the FA £34 million in lost broadcasting income in 2013.

Ticketing revenue has also dipped in more recent months. The attendance for the Euro 2016 qualifying match against San Marino was 55,990, meaning almost 35,000 fewer seats were filled than capacity, and it does not look like recovering. The identities of their other opponents in the qualifying tournament – Lithuania, Slovenia, Estonia and Switzerland – will not set fans’ blood racing.

This is a serious problem for the FA. Its strategy will have been to meet the lumpy £150 million debt-and-interest obligation between 2015 and 2018 with the renewed sale of 10-year seat licences, ideally fuelled by the promise of hosting the 2018 World Cup, reviving a good feeling around English football. It worked in 2007, when the sale of those licences generated a guaranteed future income of £210 million.

But that success is unlikely to be repeated in 2017, for a number of reasons. The excitement generated around the new Wembley cannot be repeated in a 10-year-old asset. Moreover when they were sold in 2007 it was at the height of a credit bubble. The subsequent deleveraging in the ongoing Great Recession is unlikely to abate in the next three years.

There is no external boost to the English game, since Russia is the 2018 tournament’s host. Indeed, the nature of UEFA’s new-format qualifying tournament for the European Championships is damaging to the commercial appeal of Wembley. In future few will pay substantial premiums to England matches when the national team have recently been pitted against 93rd (Estonia), 103rd (Lithuania) and 207th (San Marino) ranked teams in the world.

The FA will therefore have been relieved to read one of the front-page headlines in the London Evening Standard last week. In the article the UK government finance secretary, the Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne, said he was actively encouraging a franchise from the NFL American Football league in the US to relocate to London. “I’ve said to the NFL that anything the government can do to make this happen we will do, because I think it would be a huge boost to London,” Osborne said.

It would be a huge boost to the FA’s finance to guarantee eight NFL fixtures each year taking place at its facility, each of which will bring substantially larger crowds than England-San Marino. But that would not transform the FA’s fortunes on its own. There are other, still-more-intriguing possibilities.

Last week Ron Gourlay also left his post as Chelsea’s chief executive. The biggest inbox item for his successor will be finding an answer to the club’s stadium quandary. Roman Abramovich is ambitious for his club and would believe it could fill a 90,000-seat facility on a weekly basis.

The opportunity to rebuild Stamford Bridge is highly limited due to the lack of access points and local travel options. Wembley has no such problems and is only a 10-mile drive up the north circular, or six miles away as the crow flies. A discount purchase of Wembley, relieving the FA’s future financial headache and allowing it to host England games in a more scaleable fashion at club facilities – as it did so successfully during the Wembley construction period – would seem to suit all parties.

The structure of UEFA’s Financial Fair Play rules allows for investment in stadiums, and the increased cash flows a 90,000-seat stadium would bring would enable Chelsea to maintain their historically elevated player investment without regulatory offence. Christian Purslow, who was this week appointed Chelsea’s head of commercial operations, would no doubt also benefit in negotiations with sponsorship partners if the club had Wembley to shout about.

There are complications, such as the £120 million grant owing to the government agency Sport England if the stadium changes hands but none of them is insurmountable with the benefit of an oligarch’s money. Building Wembley cost about £1 billion all told. Receiving a ready-made 90,000-seat facility with no construction risk that could generate perhaps £120 million a year in match-day income would surely be worth £750 million to Abramovich.

That could give the FA a windfall worth perhaps £300 million and completely derisk its operations, freeing millions every year in future debt savings to boot. Time for the FA to reconsider its priorities, for the benefit of English football as a whole.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1735864250labto1735864250ofdlr1735864250owedi1735864250sni@t1735864250tocs.1735864250ttam1735864250.