“If you owe your bank a hundred pounds, you have a problem. But if you owe a million, it has.” John Maynard Keynes

Like him or loathe him – and he splits opinion as surely as Marmite – John Maynard Keynes was one of history’s greatest minds. His writing has formed the basis of the modern economic system. (Although what he taught has been treated as a piecemeal buffet from which to pick and choose according to political expediency, rather than a doctrine to be adhered to wholesale. This fact has inevitably skewed the application, outcomes and perception of Keynes’s work, which I find egregiously unfair to him.)

In his assessment of banking and the business of debt, Keynes was characteristically prophetic. When in 2007 the true extent of the counterparty risk involved in the loan books of banks in most countries in the western world became clear, the financial system suffered its greatest seizure in living memory. The effects of this shock are still being felt nearly a decade later and will be for a very long time to come.

Inevitably, with something so fundamental occurring in society at large, football did not emerge unscathed. Back in October 2008 the then chairman of the Football Association, Lord David Triesman, attacked the level of football-club indebtedness. “Not only is debt at high-risk levels, we are also in a period when transparency lies in an unmarked grave,” he said. “There is little point in thinking this now affects everyone except football. I predict, especially in today’s financial climate, it cannot go on.”

Indeed, two now-successful Premier League clubs, Southampton and Crystal Palace, were both rescued from liquidation at the hands of the banks in 2009 and 2010 respectively. Their inability to pay their debts would catch up with them. It led to a period in which retail banks scaled back very strongly on the lending they would provide to football clubs.

Even today, banks tend to refuse to offer to collateralise finance solely against stadiums, which they rightly consider to have no market value to anyone other than the club that occupies the ground. (This was something Palace’s owners were able to exploit when reuniting the club with Selhurst Park ahead of their takeover.)

So deep was the financial sector’s scepticism of football that when they approached the bond market for financial support, even Manchester United were deemed a high-risk investment. When finally they came in they were classed as unrated, “junk” bonds that left analysts highly circumspect. “Most people just won’t focus on something with far too much leverage, limited free cash flow and lumpy earnings,” said Jonathan Moore, a high-yield analyst at Evolution Securities ahead of the 2010 bond issue.

So how would Keynes assess Premier League clubs today? Are they by his measure borrowers of a hundred pounds or of a million? Who is at risk, the clubs or the banks?

The levels of debt in the Premier League have elicited a lot of comment and made a lot of headlines over the years. This is because the number is very large indeed. There are 15 clubs who played in the Premier League for at least four of the five seasons between 2009-10 and 2013-14. For the purposes of this study let’s call them the Core 15, or C15 clubs. (They were Arsenal, Aston Villa, Chelsea, Everton, Fulham, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United, Newcastle United, Stoke City, Sunderland, Tottenham Hotspur, West Bromwich Albion, West Ham United and Wigan Athletic.)

At their financial-year end in 2014, the most-recent period for which data are available, the combined debt of these 15 Premier League clubs was £1.927 billion. Now because in football we are used to dealing with numbers so large there is for most of us no reference point, it is worth giving that sum some context. So what about this? Bank of England figures show that in May 2014, a similar time to most clubs’ balance-sheet date, the gross outstanding lending secured on dwellings in the UK was £16.802bn.

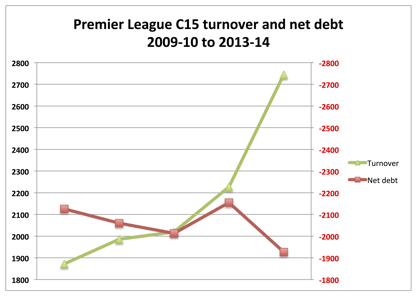

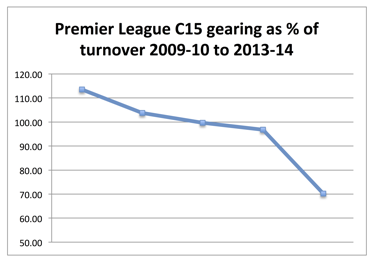

So those 15 Premier League clubs alone carried debts equivalent to 11.5% of the total amount owed by all British households on their mortgages. Back in 2010, the sum owed by the C15 Premier League clubs – higher then, at £2.125bn – had even exceeded their annual revenues. This weighed heavily on the C15 clubs, with 5.83p of every pound generated going in paying interest on their debts – repayments of the principal owed ate in to their disposable income still further. These are the figures that caused the righteous comment about indebtedness. With the effects of the financial crisis raging, the biggest clubs in the Premier League were, in terms of gearing at least, underwater.

However the danger has now very much passed. As clubs generated massive sums through the new broadcast arrangements with Sky and BT, which began in the 2013-14 season, a good proportion of it was hoarded in cash, thus deleveraging the C15’s balance sheets. Everton’s came down almost 40%, Newcastle’s almost 30%. Arsenal’s were reduced by fully 65% in that single season.

There was now a gaping disparity between revenues and debts, reducing the clubs’ gearing to much-more-manageable levels. Indeed, there are signs this rapid deleveraging has continued, with Manchester United knocking another £20.2 million off their net debt in 2014-15 and Arsenal almost eliminating theirs with another £26.9 million cash squirrelled away. It suggests that, with two of the historically most-indebted clubs reducing their burdens so substantially, the C15’s (or equivalent clubs’) overall indebtedness will continue to taper this season.

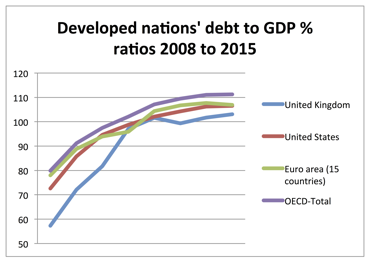

Again, it is worth giving some context. This gearing, though still high at about 70%, is encouraging for its reduction. The same cannot be said of many other debt burdens around the world.

Now, most economists would consider it preposterous to compare any business’s financial model with the finances of a sovereign nation state. Unlike businesses, nations can raise taxes from their citizens at will, giving them far-more control over their finances than businesses who are at the mercy of consumers. However the similarities between the finances of nations and those of England’s top football clubs in the 21st Century is greater than economists would at first realise.

Clubs have found the tolerance of their “citizens”, the fans, to higher “taxes” or season-ticket prices, has been very elastic indeed. There is also the capacity for revenue-raising from the still-more-lucrative source of broadcast contracts – which with the increasing globalisation of the English top league has externalised the “tax base” to other nations.

One oft-cited difference between government finances and that of the corporate world is that national treasuries’ annual budgets should keep a lid on rises in governments’ expenditure to manageable levels. But so too do football clubs have the opportunity to manage cash flows in their businesses due to the medium- and long-term nature of revenue segments like broadcast and match-day income. So, too, that of the major operational cost: employment contracts. These are facts that add up to a host of important benefits for the C15 clubs. Indeed, what developed-world government can boast a compound annual growth rate of 10.03% in its GDP between 2010 and 2015, as the C15 clubs have in their turnover?

Moreover, once next season’s Premier League deal comes on stream and raises revenues still further, C15 gearing will continue to drop from what is already a much-healthier position than it was five years ago. Add in the fact that a very large amount of the debt owed by some clubs – including substantially the most indebted of all, Chelsea, with their £1.001 billion owing – is ascribed to those clubs’ owners, and the picture around C15 finances is very rosy.

Of course it is not all plain sailing and, even for the C15, football is a risky business. In the same way that nations can face economic shocks – like the global financial crisis of 2007-8 or the recent currency crisis in Russia and elsewhere – relegation from the Premier League dangerously reduces revenues. What has now become an extended absence from the Premier League for previous C15 members Fulham and Wigan demonstrates just how the top-club status can be short lived.

Even within the top division in England it may be that the revenues fall off a cliff. A genuine and global consumer-finances crisis would damage the solvency of many clubs, affecting their ability to sell to local consumers, to export the Premier League product overseas, and to invest in the business from within their own cash flows. This, in a move that Keynes would surely recognise, would require the “central bank” of clubs’ savings to step in to cover the shortfall.

Keynes would probably admire the way our C15 clubs have organised themselves in this boom time, such that they should soon have the flexibility to weather a financial shock when it ends. Happily for the C15, with a new and still-better-funded broadcast cycle soon to begin and to last until 2019, that shock, if and when it comes, is still some way away.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745612183labto1745612183ofdlr1745612183owedi1745612183sni@t1745612183tocs.1745612183ttam1745612183.