Does the 2009-2010 Premiership mark a season that heralds revolutionary change?

Or are the changes more cosmetic?

A superficial glance may suggest that this has been a season like no other.

Portsmouth has made dubious history as the first Premiership club to go into administration and, wherever you look, clubs are in financial trouble.

You may or may not agree with Paul Elliott, the former Chelsea captain, who told me that it has been the best Premiership season since its inception in 1992. There is no denying the Premiership’s ability to produce compelling drama.

Ever since the new Champions League format came into being at the turn of the century with four English teams qualifying for the competition, the Premiership has always been three leagues rolled into one: a top four, a bunch trying to break into the top four, and then half a dozen fighting relegation.

But this year the top four has become a top two of Chelsea and Manchester United. The third team Arsenal (no trophies in five years) went into the last day facing the possibility that its third place, and with it automatic qualification for Champions League, might have been threatened by a resurgent Spurs.

And then there has been the decline of Liverpool, from second to just qualifying for the Europa League. This is quite a fall for a team that, since Bill Shankly brought them up from the old Second Division back in the 60s, has always been there or thereabouts in the title race. Add to that rich Manchester City champing at the bit having missed out on the Champions League and you have a heady brew suggesting some very radical changes.

Also note that the points gap between the top three and the fourth team continues to narrow, a trend that started a couple of seasons ago and it is easy to see why many feel the tumbrels for the old regime are rolling.

But I would urge caution in coming to such a view.

For a start football revolutions are not quite like political revolutions. In classic political revolutions hordes storm the gates, the old regime falls, the new one takes over.

Football fans, like all sporting fans, may wish for such sudden change particularly if their teams have been doing badly but that is not how it works.

Football revolutions take time, particularly when clubs are trying to progress on the upward journey. The path to power is more torturous. In contrast sporting declines can be sudden. Look at how Tottenham declined after its glory days of the 60s, Manchester United after the great Busby era, Leeds after Revie. The road back to greatness takes a lot longer.

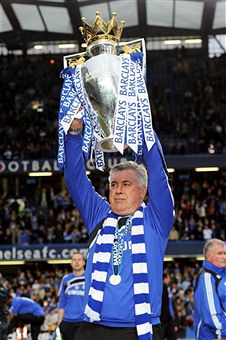

You could argue that Ancelotti’s Chelsea winning the title, while not a revolution, was a nuanced, distinct change to the team Jose Mourinho took to two titles. Chelsea of 2010 won by playing attractive football. The team that Carlo Ancelotti (pictured) has built is a team that has endeared itself, not just to blue fans, but to neutrals in the way Jose Mourniho’s team never did.

You could argue that Ancelotti’s Chelsea winning the title, while not a revolution, was a nuanced, distinct change to the team Jose Mourinho took to two titles. Chelsea of 2010 won by playing attractive football. The team that Carlo Ancelotti (pictured) has built is a team that has endeared itself, not just to blue fans, but to neutrals in the way Jose Mourniho’s team never did.

To go into the final match needing to win and then to emerge with an 8-0 victory is the sort of football I was brought up on. This was the football of the 50s and 60s when an average of three or more goals was common in English football. That is when that old cry emerged: you score four, we will score five.

But Chelsea was also more vulnerable, losing more games than a team wishing to become champion can normally afford to. It was a maxim of top flight football that any team that lost more than four games in a season could not win the title. Chelsea lost six and still won.

There is more substance to the revolution argument when you look at what is happening below Chelsea.

Here, not only for the first time since 2005 has a top four club been dislodged, but there are significant differences between 2005 and 2010.

Then Everton, in breaking through, just managed to displace Liverpool. But the top four quickly reformed and remained as it had been for much of the last decade: like a footballing Fort Knox impossible to prise open.

This time Tottenham’s breakthrough has been more like the gates being sliced open, open quite wide at that.

I can best illustrate this by comparing the top four in 2004-2005 and 2009-2010.

2004-2005 final table of top four

Chelsea – champions with 95 points, just one defeat

Arsenal – second with 83 points, 5 losses

Manchester United – third with 77 points, 5 losses

Everton – fourth with 61 points, 13 losses

Liverpool came fifth with 58 points 14 losses

2009-2010 season top four

Chelsea – champions with 86 points, 6 losses

Manchester United – second with 85 points, 7 losses

Arsenal – third with 75 points, 9 losses

Tottenham – fourth with 70 points, 10 losses

Liverpool – seventh with 63 points, 11 losses

As it happens 2005 is not a bad starting point of comparison as that was the first of the two triumphs for Mourinho.

But a glance at the tables above shows the major difference. The gap between Chelsea and Everton was a chasm, almost half a league, 34 points, but the gap between Tottenham and Chelsea, while significant, 16 points, is bridgeable, even over the course of a season.

The obvious way to bridge the gap is spending money to get players. This is where we come to the new maths of the Premiership, now that most people realise that the pre-recession spending was insane.

Ever since the Premiership started only one team has made a real breakthrough: Chelsea. Yes Newcastle threatened, yes Leeds threatened, for much of the 1992-1993 season even Norwich for a long period was second to Manchester United and finally finished third. In 1995 Blackburn sprinkled by uncle Jack Walker’s gold dust actually took the title – the only team outside of Manchester United, Arsenal and Chelsea to win the Premiership.

But since the formation of the Premier League only one true outsider has become permanent lodger on the top floor. That outsider, how odd it sounds to say it, is Chelsea. Barely admitted to the top table when the League was formed in 1992, their journey upwards began in the mid to late 90s and the key was turned when suddenly in 2003 Roman Abramovich appeared. Having looked at Tottenham, and unable to do a deal, his money transformed Chelsea and had quite an impact on other clubs finances as well.

But now there are signs that the Russian Czar of Chelsea is said to be feeling the pinch. There may be money but not quite as in the past. And to borrow that John Lewis phrase, there is another Premier League club, Manchester City, which will not knowingly be under-spent. Abu Dhabi oil means that they can blow rivals out of the water, as Harry Redknapp, the Tottenham manager, alleged they did over a transfer deal involving the London club. The economic recession has made City’s cash power even more pronounced and this means Abu Dhabi oil could indeed prove a real game-changer for City.

For Tottenham, having kept City at bay, the question is: what can they do to make the most of their opportunity. Everton could not because they did not have the financial resources.

Tottenham are, in money terms, not in City or Chelsea’s class but have enough to make a difference. There may be many fans who grumble about Tottenham chairman Daniel Levy and his football management. He found Redknapp almost by accident and in a moment of despair. His constant chopping and changing of managers, and ushering in the continental system with fanfare then abandoning it, does not say much for his football judgement. But, when it comes to money, he has run a tight, efficient ship which could be a model for other clubs. And the club should have money to spend.

And what is more important, Levy knows he has to spend if qualification for the Champions League is to give him leasehold rights, not just a holiday let which is what Everton enjoyed.

And if he needs an incentive, he should look at the parlous state of Liverpool’s finances and conclude that the Merseyside giant is going nowhere except probably down. This is the time to do a Chelsea and make such a claim for the top floor that no other tenant will be able to dislodge his team.

If he does this, then the 2009-2010 season will be as significant as the 2002-2003 season when Chelsea, having flirted with the top floor, established their rights and have not been dislodged since.

And that would be quite a British revolution.

Mihir Bose is one of the world’s most astute observers on politics in sport and, particularly, football. He formerly wrote for The Sunday Times and The Daily Telegraph and until recently was the BBC’s head sports editor.

.jpg)